Instrumentation Selection for Vibration Testing: A Comprehensive Guide

A systematic framework for selecting accelerometers, DAQ systems, and signal conditioning for modal testing, acoustic testing, vibration qualification, shock testing, and pyroshock environments. Includes comparison tables, checklists, and decision flowcharts.

Instrumentation Selection for Vibration Testing: A Comprehensive Guide

Selecting the right instrumentation for vibration testing is one of the most critical decisions an engineer makes before any test campaign. Poor instrumentation choices can lead to clipped data from sensors that saturate, signals buried in the noise floor, aliased frequency content from inadequate sample rates, or corrupted measurements from mass loading effects. Each of these failures can invalidate an entire test campaign, costing significant time and resources while potentially missing critical structural dynamics information.

This guide provides a systematic framework for instrumentation selection across the spectrum of vibration testing applications, including modal testing and ground vibration testing (GVT), structural response measurement in reverberant acoustic chambers, vibration qualification testing for components, and shock testing including pyroshock environments.

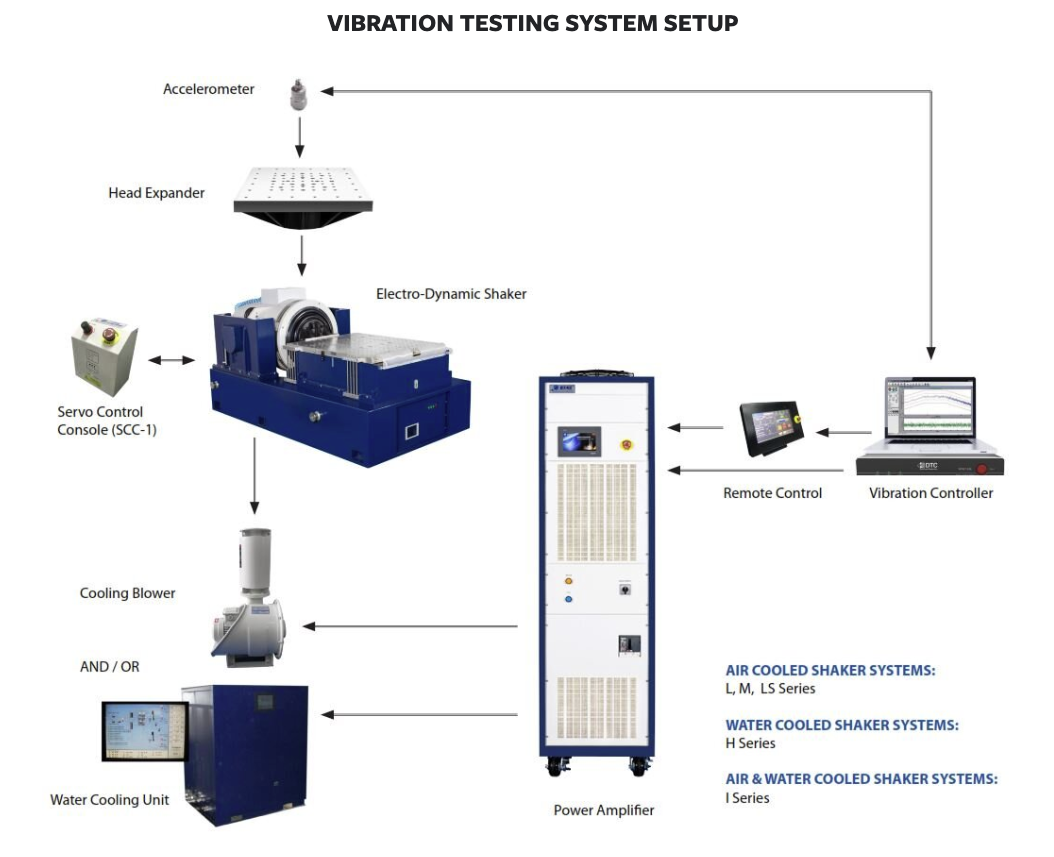

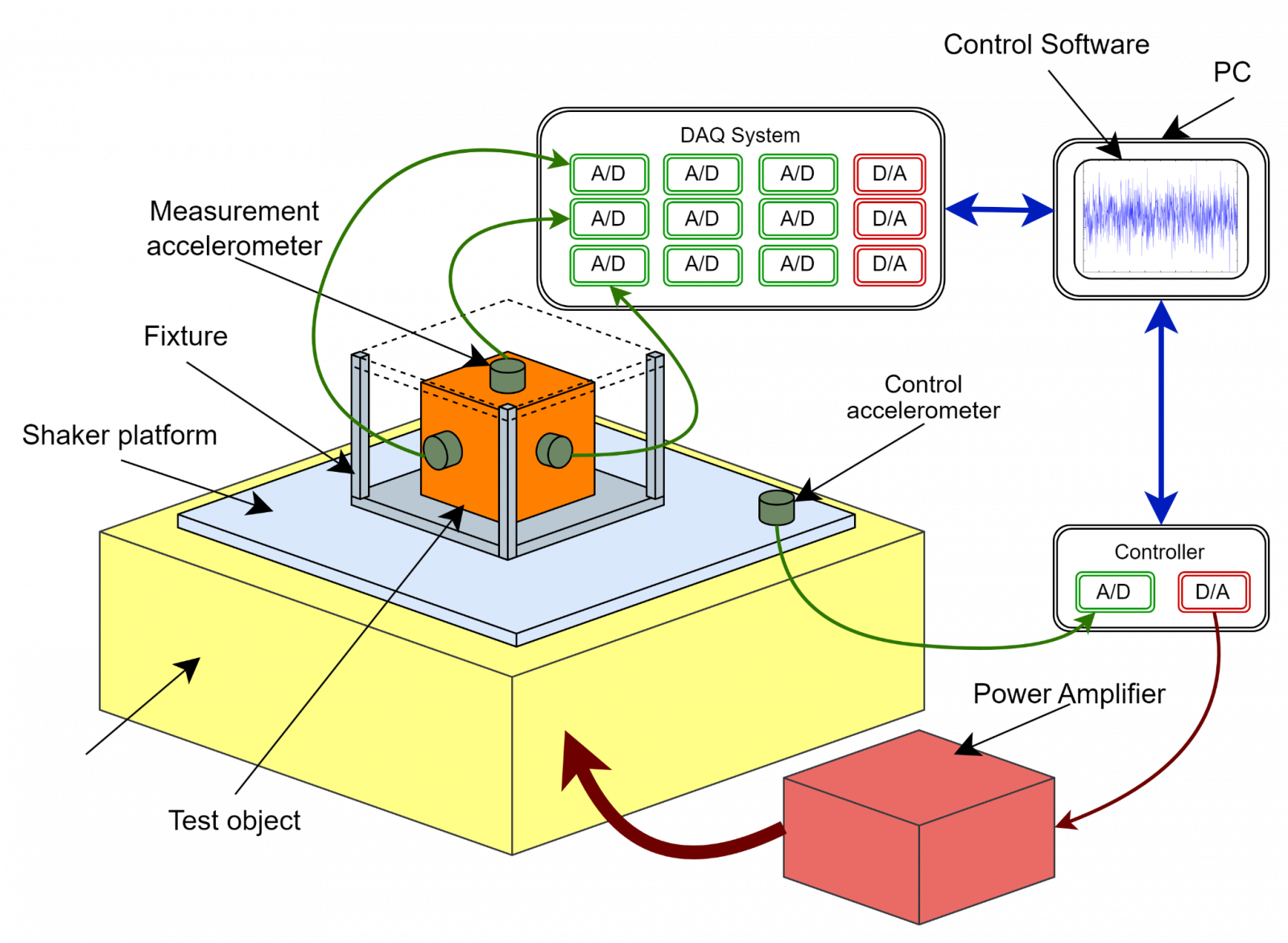

A complete vibration test system includes the electrodynamic shaker, power amplifier, controller, and data acquisition system.

A complete vibration test system includes the electrodynamic shaker, power amplifier, controller, and data acquisition system.

Part 1: Foundational Concepts in Vibration Instrumentation

Accelerometer Types and Operating Principles

The accelerometer is the most common transducer used in vibration testing, and understanding the different types is essential for proper selection. Each accelerometer type has distinct operating principles that make it suitable for specific applications.

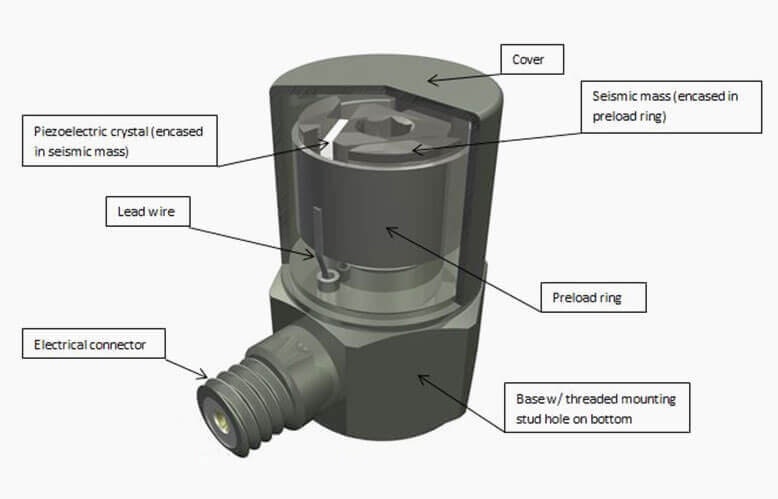

Cutaway view of a piezoelectric accelerometer showing the seismic mass, piezoelectric crystal, and internal components.

Cutaway view of a piezoelectric accelerometer showing the seismic mass, piezoelectric crystal, and internal components.

Piezoelectric (PE) accelerometers are the most frequently used type in vibration testing. In a PE accelerometer, a seismic mass pushes against a piezoelectric crystal element, which generates an electric charge proportional to the applied acceleration. PE accelerometers excel in high-frequency applications (typically from less than 3 Hz up to 30 kHz) and can operate at temperatures up to 260°C for standard versions and 650°C for high-temperature variants. They are well-suited for both vibration and shock testing due to their wide dynamic range and robust construction.

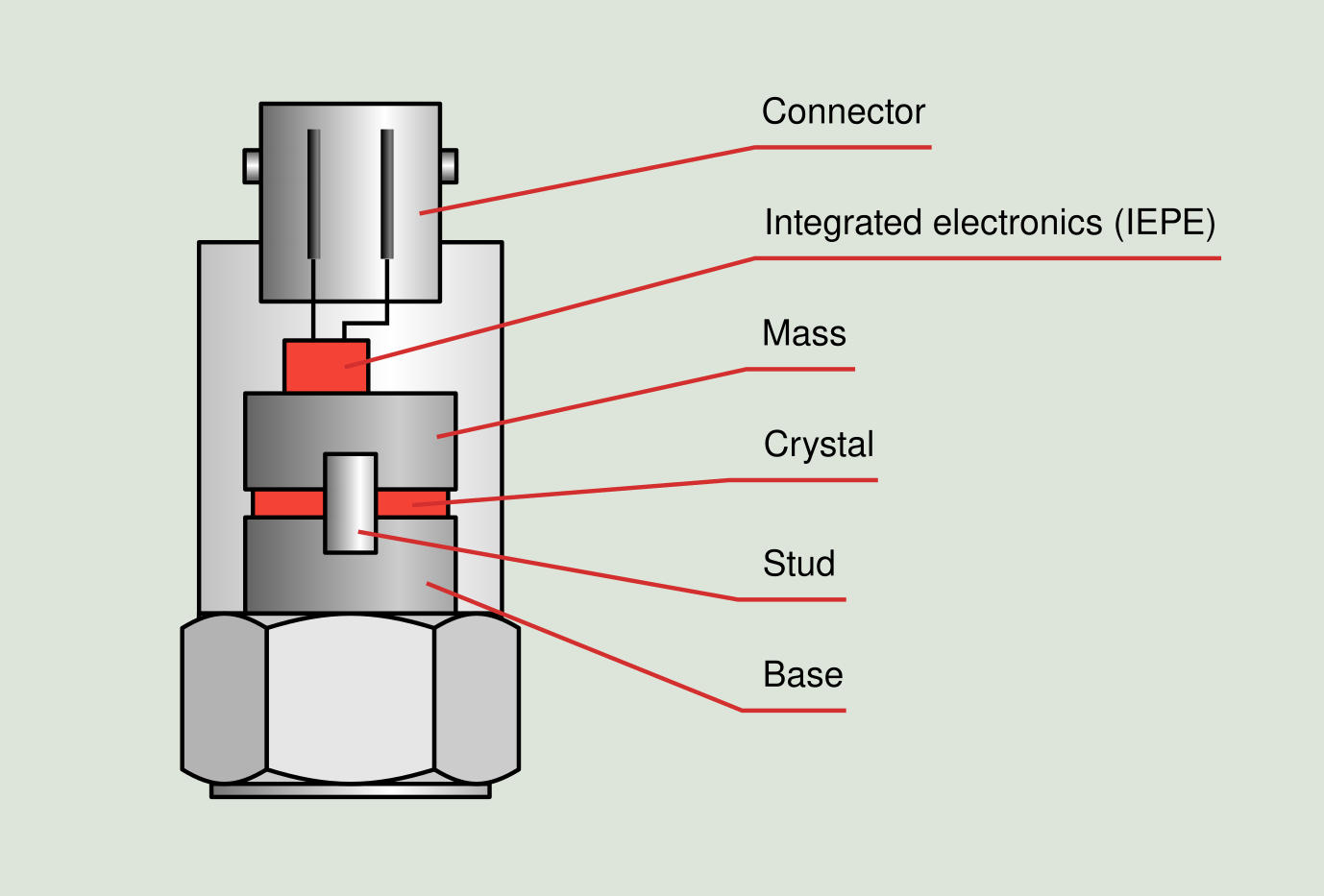

IEPE (Integrated Electronics Piezoelectric) accelerometers, also known as ICP sensors, contain internal electronics that convert the high-impedance charge signal into a low-impedance voltage output. This integration provides significant advantages: the voltage signal can be transmitted through standard coaxial cables with greater resistance to electrical noise and cable interference.

Internal structure of an IEPE accelerometer showing the integrated electronics, piezoelectric crystal, seismic mass, and connector.

Internal structure of an IEPE accelerometer showing the integrated electronics, piezoelectric crystal, seismic mass, and connector.

Charge output accelerometers generate a signal directly from the piezoelectric element without internal signal conditioning. This high-impedance signal requires a low-noise cable and an external charge amplifier for signal conditioning. While the setup is more complex, charge accelerometers offer significant advantages: they can operate at temperatures up to 260°C and beyond, and the external charge amplifier allows variable gain, time constant adjustment, and filtering flexibility.

Piezoresistive (PR) accelerometers use a variable resistor attached to a seismic mass. When the mass moves, the resistance changes, producing a proportional current change. PR accelerometers are particularly useful for shock applications where sudden or extreme vibration is anticipated, and they provide DC response capability that piezoelectric types cannot offer.

| Accelerometer Type | Frequency Range | Temperature Range | Best Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Piezoelectric (PE) | <3 Hz to 30 kHz | Up to 260°C (650°C high-temp) | General vibration, high temperature |

| IEPE/ICP | <3 Hz to 30 kHz | Up to 125°C (185°C high-temp) | General vibration, simplified setup |

| Charge Output | <3 Hz to 30 kHz | Up to 260°C+ | High temperature, variable gain needed |

| Piezoresistive | DC to 10 kHz | Ambient | Shock, DC response required |

| Capacitive/MEMS | DC to 1 kHz | Ambient | Low frequency, structural monitoring |

The Sensitivity-Range Trade-off

Accelerometer sensitivity is perhaps the most critical specification to understand, as it directly determines the measurement range and signal quality. Sensitivity is expressed in millivolts per g (mV/g) for voltage-output accelerometers or picocoulombs per g (pC/g) for charge-output types.

The fundamental trade-off is straightforward: higher sensitivity provides better signal-to-noise ratio for low-level measurements but limits the maximum measurable acceleration. A 100 mV/g accelerometer is typically limited to approximately 50g measurements before the output voltage exceeds the sensor's or DAQ system's input range. Conversely, a 10 mV/g accelerometer can measure up to approximately 500g but produces only 1 mV when measuring 0.1g—a signal that may be lost in the noise floor of many data acquisition systems.

Consider a practical example: measuring 0.1g with a 10 mV/g sensor produces only 1 mV of output, which may be below the noise floor of some DAQ systems. The same measurement with a 100 mV/g sensor produces 10 mV—a much more robust signal. However, if the test article experiences a resonance at 100g, the 100 mV/g sensor would attempt to output 10 V, likely exceeding system limits and causing signal clipping.

Frequency Response and Usable Bandwidth

Every accelerometer has a characteristic frequency response that defines its usable measurement range. The frequency response curve shows how the accelerometer's sensitivity varies with frequency, and understanding this curve is essential for accurate measurements.

Typical accelerometer frequency response showing the flat region, resonant peak, and usable bandwidth limits.

Typical accelerometer frequency response showing the flat region, resonant peak, and usable bandwidth limits.

The resonant frequency of an accelerometer is the frequency at which the internal seismic mass-spring system resonates, causing a dramatic increase in sensitivity followed by a rapid roll-off. The usable bandwidth is typically defined as the frequency range over which the sensitivity remains within ±5% or ±3 dB of the nominal value. As a rule of thumb, the usable upper frequency limit is approximately one-third to one-fifth of the resonant frequency.

Mass Loading Considerations

When an accelerometer is mounted on a test structure, it adds mass that can alter the structure's dynamic response. This effect, known as mass loading, is particularly significant for lightweight structures or when measuring high-frequency modes.

The general rule is that the accelerometer mass should not exceed 10% of the effective mass of the structure at the measurement point. For very lightweight structures such as printed circuit boards, miniature accelerometers weighing as little as 0.19 grams may be required.

Part 2: Data Acquisition System Fundamentals

Bit Resolution and Dynamic Range

The data acquisition system (DAQ) converts the analog accelerometer signal into digital data for analysis. The bit resolution of the analog-to-digital converter (ADC) determines how finely the signal can be discretized, directly affecting the system's ability to capture both large and small signal components simultaneously.

Modern modular DAQ systems like the Dewesoft KRYPTON provide high channel count with 24-bit resolution for vibration measurements.

Modern modular DAQ systems like the Dewesoft KRYPTON provide high channel count with 24-bit resolution for vibration measurements.

| Bit Resolution | Discrete Levels | Theoretical Dynamic Range |

|---|---|---|

| 12-bit | 4,096 | 72 dB |

| 16-bit | 65,536 | 96 dB |

| 24-bit | 16,777,216 | 144 dB |

For general vibration applications, a dynamic range greater than 100 dB with at least 200 kS/s sample rate is typically adequate. However, for shock, noise, and vibration applications where signals may span from micro-g background levels to hundreds of g's during transients, a dynamic range of 120 to 160 dB is highly desirable.

Signal-to-Noise Ratio and Noise Floor

The signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) determines whether small signals can be distinguished from the measurement system's inherent noise. The noise floor of a DAQ system is typically specified in microvolts or as an equivalent acceleration level for a given accelerometer sensitivity.

When selecting instrumentation, calculate the expected minimum signal level and ensure it is at least 10-20 dB above the system noise floor for reliable measurements. For critical measurements, aim for 30 dB or more of margin.

Sample Rate and the Nyquist Criterion

The Nyquist theorem states that a signal must be sampled at a rate at least twice the highest frequency component present in the signal to avoid aliasing. In practice, the sample rate should be significantly higher—typically 5 to 10 times the highest frequency of interest—to accurately capture waveform shape and ensure adequate frequency resolution in spectral analysis.

| Frequency of Interest | Minimum Sample Rate (Nyquist) | Recommended Sample Rate |

|---|---|---|

| 100 Hz | 200 Hz | 500-1,000 Hz |

| 1,000 Hz | 2,000 Hz | 5,000-10,000 Hz |

| 10,000 Hz | 20,000 Hz | 50,000-100,000 Hz |

Part 3: Hardware Frequency Response Function

Understanding Accelerometer FRF

The hardware frequency response function (FRF) of an accelerometer describes how its output varies with frequency for a constant input acceleration. An ideal accelerometer would have perfectly flat response across all frequencies, but real accelerometers exhibit frequency-dependent behavior due to their mechanical construction.

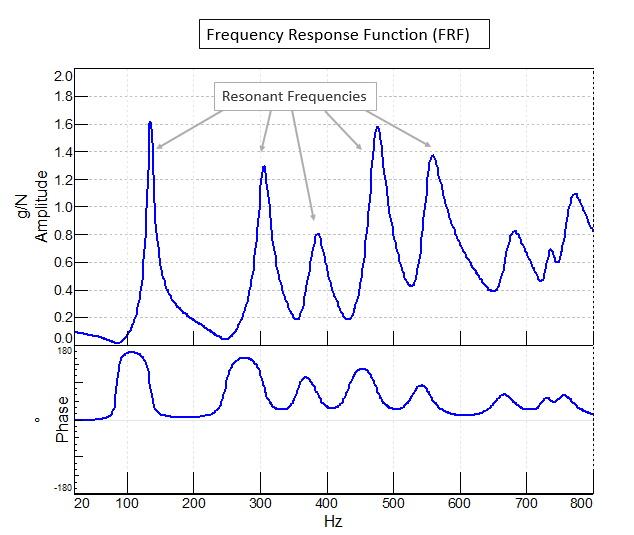

Frequency Response Function (FRF) showing resonant frequencies as peaks in the magnitude plot and corresponding phase shifts.

Frequency Response Function (FRF) showing resonant frequencies as peaks in the magnitude plot and corresponding phase shifts.

The typical accelerometer FRF shows three regions: a flat region at low to mid frequencies where sensitivity is constant, a roll-off region at very low frequencies (for AC-coupled sensors), and a resonance region at high frequencies where sensitivity increases dramatically before dropping off.

Phase Considerations for Modal Testing

Phase accuracy is particularly critical for modal testing and FRF measurements, where the phase relationship between excitation and response determines mode shapes and damping. Phase shift in an accelerometer begins well before amplitude deviation becomes significant—often at frequencies as low as one-tenth of the resonant frequency.

For modal testing, ensure that all accelerometers in the measurement set have matched phase response across the frequency range of interest. Using accelerometers of the same model and sensitivity helps ensure phase matching.

Part 4: Test-Specific Instrumentation Requirements

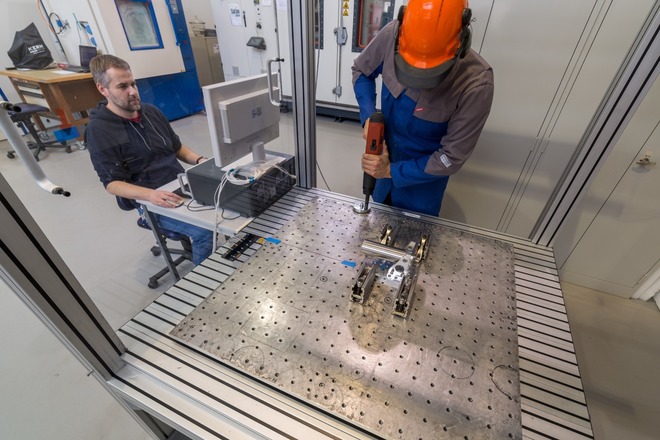

Modal Testing and Ground Vibration Testing (GVT)

Modal testing aims to characterize a structure's natural frequencies, mode shapes, and damping ratios through measurement of frequency response functions. Ground vibration testing (GVT) applies these techniques to full-scale structures such as aircraft, where hundreds of measurement points may be required to capture all modes of interest.

Ground vibration testing of an aircraft requires hundreds of accelerometers and careful planning to capture all structural modes.

Ground vibration testing of an aircraft requires hundreds of accelerometers and careful planning to capture all structural modes.

Test Objectives: Identify natural frequencies, extract mode shapes, determine damping ratios, and validate finite element models.

Typical Frequency Range: Modal tests typically cover 1 to 200 Hz for large structures and up to 1,000 Hz for aircraft and smaller components.

Amplitude Levels: Modal tests use low-level excitation, typically 0.1 to 1g, to maintain linear structural behavior.

Impact hammer testing is a common method for measuring FRFs on smaller structures and components.

Impact hammer testing is a common method for measuring FRFs on smaller structures and components.

| Parameter | Requirement | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | 100 mV/g (high) | Low excitation levels require high sensitivity for adequate SNR |

| Frequency Response | Flat to 2× highest mode | Ensures accurate amplitude and phase across measurement band |

| Low-Frequency Response | Down to 1 Hz or lower | Captures fundamental modes of large structures |

| Phase Matching | <5° between channels | Critical for accurate mode shape extraction |

| Coherence | >0.9 at resonances | Indicates quality FRF measurements |

Reverberant Acoustic Chamber Testing

Reverberant acoustic testing subjects hardware to high-intensity sound fields that simulate launch or flight acoustic environments. The test measures structural response to the acoustic excitation, typically for spacecraft and launch vehicle components.

Reverberant acoustic chamber testing at ESA subjects spacecraft to high-intensity sound fields simulating launch environments.

Reverberant acoustic chamber testing at ESA subjects spacecraft to high-intensity sound fields simulating launch environments.

Test Objectives: Verify structural integrity under acoustic loading, measure structural response for comparison with analysis predictions, and qualify hardware for flight.

Typical Frequency Range: Acoustic tests typically cover 25 to 10,000 Hz, spanning the range of significant acoustic energy in launch environments.

NASA's Plum Brook Station acoustic test facility can generate sound pressure levels exceeding 160 dB for full-scale spacecraft testing.

NASA's Plum Brook Station acoustic test facility can generate sound pressure levels exceeding 160 dB for full-scale spacecraft testing.

| Parameter | Requirement | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Accelerometer Sensitivity | 10-100 mV/g | Must accommodate wide range of response levels |

| Frequency Bandwidth | 25-10,000 Hz minimum | Covers acoustic excitation range |

| Microphones | Pressure-field type | Measures acoustic environment in reverberant field |

| DAQ Dynamic Range | >100 dB | Captures both low and high response levels |

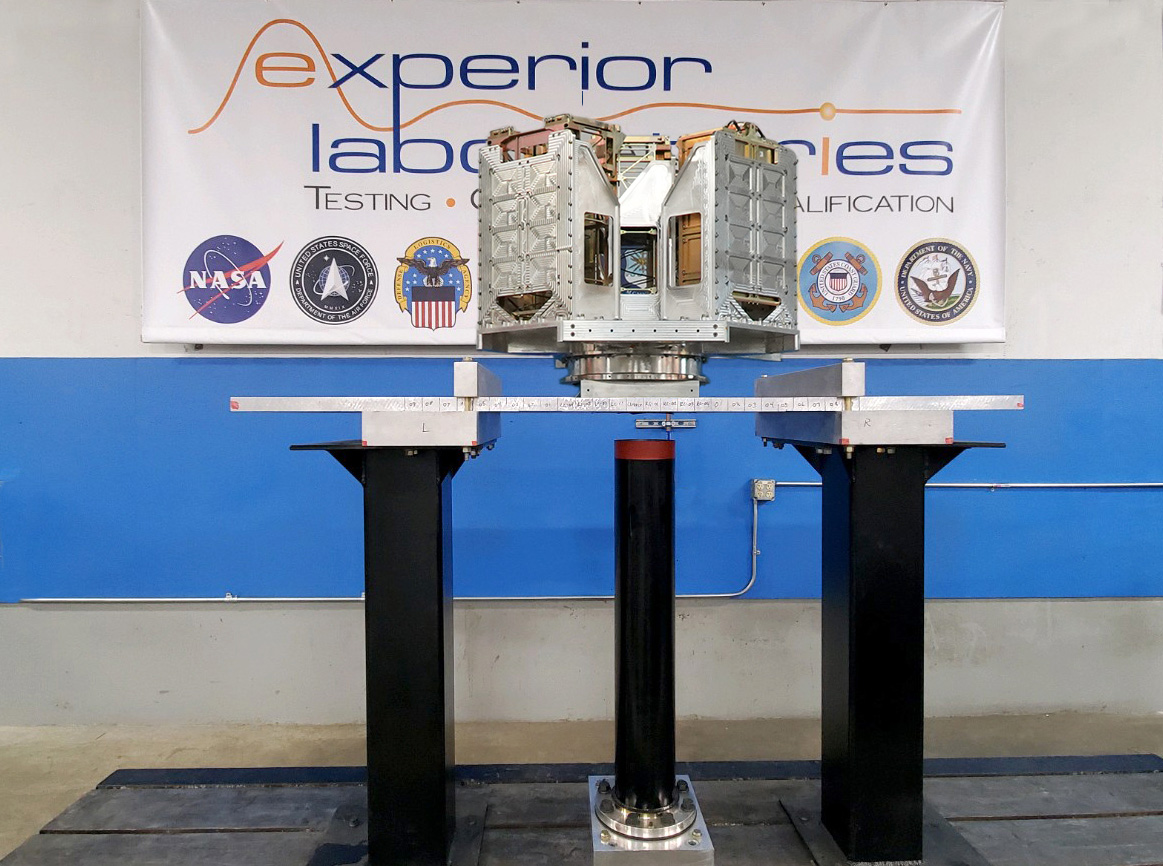

Vibration Qualification Testing

Vibration qualification testing verifies that hardware can survive the vibration environments encountered during transportation, handling, and operation. Tests may use sinusoidal, random, or combined excitation depending on the applicable specification.

A typical vibration qualification test setup showing the shaker, fixture, test article, control accelerometer, and DAQ system.

A typical vibration qualification test setup showing the shaker, fixture, test article, control accelerometer, and DAQ system.

Test Objectives: Demonstrate hardware functionality and structural integrity after exposure to specified vibration environments.

Typical Frequency Range: Most vibration qualification tests cover 20 to 2,000 Hz, which encompasses the primary structural response range for most hardware.

| Parameter | Requirement | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Control Accelerometer | At fixture/article interface | Defines input to test article |

| Response Accelerometers | On test article | Monitors structural response |

| Sensitivity | 10-100 mV/g | Accommodates moderate to high levels |

| Frequency Bandwidth | 20-2,000 Hz minimum | Covers standard qualification range |

Shock Testing

Shock testing subjects hardware to transient acceleration pulses that simulate handling drops, pyrotechnic events, transportation impacts, or operational shocks. Unlike sinusoidal or random vibration testing which applies continuous excitation, shock testing delivers a single high-amplitude, short-duration event that stresses the hardware in fundamentally different ways.

The Shock Response Spectrum (SRS) is the standard method for specifying and analyzing shock environments. It is important to understand that the SRS is an analysis tool—a way of characterizing the damage potential of a shock transient—not a test method itself. The SRS represents the peak response of an array of single-degree-of-freedom oscillators to the measured time history, providing a frequency-domain representation of the shock severity.

Shock testing verifies hardware can survive transient shock events. The SRS analysis characterizes the damage potential across frequency.

Shock testing verifies hardware can survive transient shock events. The SRS analysis characterizes the damage potential across frequency.

Test Objectives: Verify hardware survives shock events without damage or malfunction, and characterize the shock environment for comparison with specification requirements.

Shock Test Methods

Shaker shock uses an electrodynamic or hydraulic shaker to generate controlled shock pulses. The shaker applies a programmed waveform—typically a half-sine, terminal peak sawtooth, or trapezoidal pulse—to the test article. Shaker shock provides excellent repeatability and control but is limited in amplitude (typically less than 100g) and cannot replicate the high-frequency content of pyrotechnic events.

Drop shock releases the test article or fixture from a specified height onto a programmed surface. The impact surface characteristics (steel, felt, sand) and drop height determine the shock pulse shape and amplitude. Drop testing can achieve higher g-levels than shaker shock and is commonly used for packaging qualification and MIL-STD-810 testing.

Impact shock uses a pneumatic or mechanical hammer to strike the test fixture, generating a shock pulse that propagates through the structure to the test article. This method can produce higher amplitudes than shaker shock while maintaining reasonable control over the pulse characteristics.

Pyrotechnic shock (pyroshock) addresses the extreme, high-frequency transients generated by pyrotechnic devices such as explosive bolts, separation nuts, and linear shaped charges. These events produce accelerations that can exceed 100,000g with significant energy content above 10 kHz—far beyond what mechanical shock methods can replicate. Pyroshock testing requires either actual pyrotechnic devices or specialized simulators such as resonant fixtures or tuned beam assemblies.

Pyroshock testing simulates the extreme transients from pyrotechnic separation devices on spacecraft.

Pyroshock testing simulates the extreme transients from pyrotechnic separation devices on spacecraft.

Instrumentation Requirements by Shock Type

The instrumentation requirements vary significantly across shock test methods due to the different amplitude and frequency content involved.

| Parameter | Shaker/Drop/Impact Shock | Pyrotechnic Shock |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Amplitude | 100-10,000g | 1,000-100,000g |

| Frequency Content | 100-10,000 Hz | 100-100,000 Hz |

| Sensitivity | 1-10 mV/g | 0.1-1 mV/g |

| Resonant Frequency | >50 kHz | >100 kHz |

| Accelerometer Type | PE or PR | PR preferred |

| DAQ Sample Rate | 50-100 kHz | >200 kHz |

| Key Challenge | High g-range without saturation | Extreme frequency content |

| Primary Standard | MIL-STD-810 | NASA-STD-7003 |

For mechanical shock methods (shaker, drop, impact), piezoelectric accelerometers with 1-10 mV/g sensitivity typically provide adequate range while maintaining reasonable signal levels. The resonant frequency should exceed 50 kHz to prevent accelerometer resonance from corrupting the measurement.

For pyrotechnic shock, piezoresistive accelerometers are strongly preferred due to their superior high-frequency response and absence of the resonance issues that plague piezoelectric sensors in this regime. Sensitivities of 0.1-1 mV/g are required to prevent saturation at extreme g-levels, and the DAQ system must sample at rates exceeding 200 kHz to capture frequency content to 100 kHz per the Nyquist criterion.

Part 5: Summary Comparison Table

The following table summarizes instrumentation requirements across the five test types discussed in this guide.

| Parameter | Modal/GVT | Acoustic | Vib Qual | Shock Testing |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency Range | 1-1,000 Hz | 25-10,000 Hz | 20-2,000 Hz | 100-10,000 Hz |

| Typical Amplitude | 0.1-1g | 1-50g | 5-50g RMS | 100-10,000g |

| Sensitivity | 100 mV/g | 10-100 mV/g | 10-100 mV/g | 1-10 mV/g |

| Accelerometer Type | IEPE | IEPE | IEPE | PE or PR |

| DAQ Dynamic Range | >100 dB | >100 dB | >100 dB | >120 dB |

| Sample Rate | 2-5 kHz | 25-50 kHz | 5-10 kHz | 50-100 kHz |

| Key Challenge | Phase accuracy | Wide bandwidth | Temperature | High g-range |

| Primary Standard | — | NASA-STD-7001 | MIL-STD-810 | MIL-STD-810 |

Part 6: Instrumentation Selection Checklist

Use this checklist to systematically work through the instrumentation selection process for any vibration test.

Pre-Test Planning

| Step | Action |

|---|---|

| 1 | Define test objectives and success criteria |

| 2 | Identify applicable test standards and specifications |

| 3 | Determine frequency range of interest |

| 4 | Estimate minimum expected acceleration level |

| 5 | Estimate maximum expected acceleration level (including resonances) |

Accelerometer Selection

| Step | Action |

|---|---|

| 6 | Calculate required sensitivity based on amplitude range |

| 7 | Verify accelerometer bandwidth covers frequency range (with margin) |

| 8 | Check accelerometer resonant frequency (>3× max frequency) |

| 9 | Verify mass loading constraint (<10% of local mass) |

| 10 | Confirm temperature compatibility with test environment |

| 11 | Select accelerometer type (IEPE, charge, PR) based on requirements |

DAQ System Configuration

| Step | Action |

|---|---|

| 12 | Verify DAQ dynamic range meets requirements |

| 13 | Calculate required sample rate (>5× max frequency) |

| 14 | Confirm anti-aliasing filter settings |

| 15 | Select appropriate input voltage range |

| 16 | Verify channel count and synchronization capability |

Signal Conditioning and Cabling

| Step | Action |

|---|---|

| 17 | Select appropriate cables (low-noise for charge sensors) |

| 18 | Plan cable routing to minimize noise pickup |

| 19 | Verify connector compatibility |

| 20 | Configure charge amplifiers if using charge accelerometers |

| 21 | Check for ground isolation requirements |

Verification and Documentation

| Step | Action |

|---|---|

| 22 | Verify accelerometer calibration is current |

| 23 | Perform system-level verification (end-to-end check) |

| 24 | Document complete instrumentation configuration |

| 25 | Record serial numbers and calibration dates |

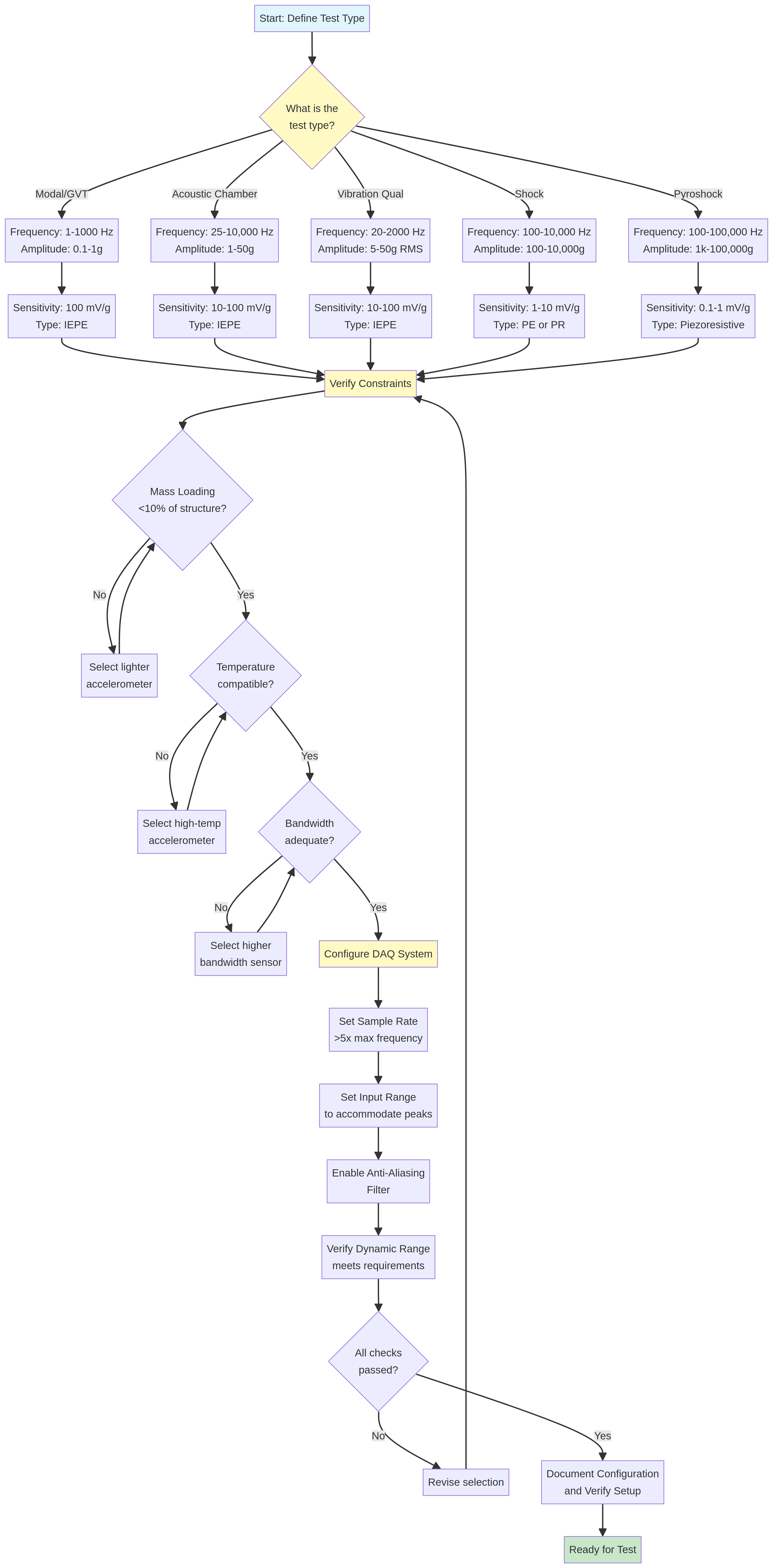

Part 7: Instrumentation Selection Flowchart

The following flowchart provides a decision tree for accelerometer selection based on test type and requirements.

Decision flowchart for selecting accelerometers based on test type, frequency range, and amplitude requirements.

Decision flowchart for selecting accelerometers based on test type, frequency range, and amplitude requirements.

Part 8: Common Pitfalls and Best Practices

Signal Clipping

Problem: Accelerometer output exceeds DAQ input range, causing flat-topped waveforms and corrupted data.

Prevention: Estimate maximum expected acceleration including resonance amplification (often 10-50× input level). Select sensitivity and DAQ range to accommodate peaks with margin. Monitor for clipping during test and adjust if necessary.

Noise Floor Issues

Problem: Low-level signals are buried in system noise, preventing accurate measurement of small responses.

Prevention: Calculate expected minimum signal level and verify it exceeds the system noise floor by at least 20 dB. Use higher sensitivity accelerometers for low-level measurements. Minimize cable length and use shielded cables.

Aliasing

Problem: High-frequency content folds back into the measurement band, appearing as spurious low-frequency content.

Prevention: Always use anti-aliasing filters. Set sample rate to at least 5× the highest frequency of interest. Verify filter cutoff frequency is appropriate for the selected sample rate.

Mass Loading

Problem: Accelerometer mass alters the structure's dynamic response, shifting frequencies and changing mode shapes.

Prevention: Verify accelerometer mass is less than 10% of local structural mass. Use miniature accelerometers for lightweight structures. Consider mass loading effects when comparing test results to analysis.

Cable Noise (Triboelectric Effect)

Problem: Cable movement generates spurious signals, particularly in charge-mode systems.

Prevention: Use low-noise cables for charge accelerometers. Secure cables to prevent movement during test. Keep cable lengths as short as practical. Consider IEPE accelerometers to minimize cable sensitivity.

Conclusion

Instrumentation selection for vibration testing requires a systematic approach that considers the specific requirements of each test type. The key parameters—frequency range, amplitude range, accelerometer sensitivity, and DAQ specifications—are interconnected, and optimizing one often involves trade-offs with others.

Modal testing demands high sensitivity and excellent low-frequency response for accurate FRF measurements. Acoustic testing requires wide bandwidth to capture the full spectrum of structural response. Vibration qualification testing needs robust instrumentation that can handle moderate to high levels across the standard 20-2,000 Hz range. Shock testing pushes toward lower sensitivity and higher bandwidth, while pyroshock testing represents the extreme case requiring specialized instrumentation capable of capturing 100,000g transients with frequency content to 100 kHz.

By following the systematic approach outlined in this guide—defining requirements, selecting appropriate sensors, configuring the DAQ system, and verifying the complete measurement chain—engineers can ensure that their instrumentation captures the data needed to characterize structural dynamics, qualify hardware for service, and validate analytical predictions.

Try It Yourself

Use our interactive tools to apply these concepts:

- G-RMS Tool - Calculate G-RMS, velocity, and displacement from PSD spectra

- SRS Tool - Compute shock response spectra from time history data

- Mesh Calculator - Determine element sizing based on wavelength requirements

This tutorial is part of the VS&A All Day engineering resource series.

References

[1] Vibration Research, "Accelerometer Selection for Vibration Testing"

[2] DJB Instruments, "Accelerometer Selection Guide"

[3] Dewesoft, "How to Choose the Right Data Acquisition System"

[4] Dewesoft, "Measuring Frequency Response Function (FRF)"

[5] M.W. Kehoe and L.C. Freudinger, "Aircraft Ground Vibration Testing at the NASA Dryden Flight Research Facility," NASA Technical Memorandum 104275, 1994

[6] NASA, "NASA-STD-7001: Payload Vibroacoustic Test Criteria"

[7] Department of Defense, "MIL-STD-810H: Environmental Engineering Considerations and Laboratory Tests"

[8] NASA, "NASA-STD-7003A: Pyroshock Test Criteria"