Vibration, Shock,

and Acoustics

Engineering Cheat Sheet

01. Core Acoustics & dB Fundamentals

Sound Pressure Level (SPL)

Logarithmic measure of effective sound pressure relative to a reference value.

- = root mean square sound pressure

- = reference sound pressure

| Medium | Reference Pressure | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Air | Threshold of human hearing at 1 kHz | |

| Water | Underwater acoustics standard (ISO) |

Wave Equation

Governs propagation of acoustic pressure disturbances through a medium.

- = acoustic pressure (Pa)

- = speed of sound (m/s)

- = Laplacian operator

02. SDOF Dynamics

Dynamic Magnification Factor (DMF)

Ratio of dynamic response amplitude to static deflection under the same force magnitude.

- = frequency ratio

- = static deflection

DMF ≈ 1

Stiffness controlled

DMF = Q = 1/(2ζ)

Resonance (max)

DMF ≈ 1/r²

Mass controlled

Phase Angle ()

- : (Stiffness controlled)

- : (Resonance)

- : (Mass controlled)

Transmissibility

Base excitation to response:

03. Damping Types

Viscous Damping

Force proportional to velocity. Ideal for fluids/dashpots.

Structural (Hysteretic) Damping

Energy dissipated per cycle is independent of frequency. Used for solids/metals.

(at resonance)

Coulomb (Dry Friction) Damping

Constant force opposing motion.

Q Factor & Loss Factor

Valid for light damping ().

04. MDOF Dynamics

Matrix Equation of Motion

- = Mass matrix (n×n)

- = Damping matrix (n×n)

- = Stiffness matrix (n×n)

- = Displacement vector (n×1)

Eigenvalue Problem (Free Vibration)

Yields n natural frequencies and mode shapes .

Modal Superposition

Transform to modal coordinates :

Where = modal matrix (columns are mode shapes).

Modal Vector Interpretation

A mode shape describes the relative displacement pattern when the system vibrates at frequency .

- Amplitude meaning: Only the ratio between DOFs matters, not absolute values. Mode shapes are typically normalized (mass-normalized: , or max=1.0).

- Sign: Positive/negative indicates in-phase/out-of-phase motion between DOFs.

- Zero crossings: Nodes where that DOF has no motion for that mode.

05. Force Balance (Beam Theory)

Euler-Bernoulli Beam Equation:

Relationships

Force/Moment Balance

Boundary Conditions

| Type | Deflection () | Slope () | Moment () | Shear () |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed | 0 | 0 | ||

| Pinned | 0 | 0 | ||

| Free | 0 | 0 |

06. Random Vibration

Miles' Equation

Estimates RMS response of SDOF system to flat random input.

- Flat input spectrum near

- Light damping

- SDOF response dominated by resonance

G-RMS from PSD

Overall RMS acceleration computed by integrating the PSD over frequency.

Note: Convert g² to (in/s²)² or (m/s²)² before integrating for velocity/displacement.

07. Vibration Statistics

Distributions

| Type | Description | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|

| Gaussian | Random vibration instantaneous values. | 3.0 |

| Rayleigh | Peak values of narrowband random. | - |

| Sine | Harmonic vibration ("Bathtub" PDF). | 1.5 |

Sigma () Peaks

Probability of exceeding in Gaussian process:

- 1

68.27% - 2

95.45% - 3

99.73%

08. VRS & Extreme Response Spectrum

Vibration Response Spectrum (VRS)

Plot of the RMS response of a series of SDOF oscillators to a random input.

| Term | Definition | Units |

|---|---|---|

| RMS response at natural frequency | g (or m/s²) | |

| SDOF transfer function (DMF) | dimensionless | |

| Input Power Spectral Density | g²/Hz |

Extreme Response Spectrum (ERS)

Estimates the maximum expected peak response over a duration .

- = RMS Response (from VRS)

- = Zero-crossing rate

- = Exposure duration (seconds)

09. Acoustic Source Models & Correlation

Acoustic Sources

| Type | Description | Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Monopole | Pulsating sphere, omnidirectional. | Low freq exhaust, small components. |

| Dipole | Two out-of-phase monopoles. | Fan noise, flow separation. |

| Plane Wave | Uniform wavefront, single direction. | Far-field sources, wind tunnels. |

| Diffuse Field | Random incidence, uniform energy. | Reverberant chambers, launch bays. |

What is Spatial Correlation?

Spatial correlation describes how pressure fluctuations at two points relate to each other. A correlation of 1 means perfectly in-phase (coherent), 0 means uncorrelated (random phase). Why it matters: Correlated pressures add constructively, producing higher structural response than uncorrelated pressures of the same magnitude. Accurate correlation modeling is critical for predicting vibration response to distributed acoustic and aerodynamic loads.

Turbulent Boundary Layer (TBL)

Fluctuating pressure on surface due to flow.

- = Dynamic Pressure

- = Displacement Thickness

- Used for: Aircraft fuselage, fairings, high-speed trains.

TBL Correlation: Corcos Model

Spatial correlation of TBL pressure fluctuations:

- = Streamwise, spanwise separation

- , (correlation lengths)

- , (Corcos constants)

- (convection velocity)

Physical interpretation: TBL correlation decays exponentially with separation distance. Correlation length decreases with frequency (high-freq eddies are smaller). Streamwise correlation is higher than spanwise due to convecting turbulent structures. The phase term captures the convection of pressure patterns downstream.

Diffuse Acoustic Field (DAF)

Uniform acoustic energy arriving from all directions with random phase.

- = Source Power (W)

- = Total Absorption (m² Sabins)

DAF Spatial Correlation

Correlation between two points in a diffuse acoustic field:

- = Separation distance between points

- = Acoustic wavenumber

- (perfect correlation at same point)

- First zero at (half wavelength)

Physical interpretation: DAF correlation follows a sinc function, oscillating and decaying with distance. Unlike TBL, DAF has no preferred direction—correlation depends only on separation distance, not orientation. Points separated by half a wavelength are uncorrelated. At low frequencies (large λ), correlation extends over larger areas, causing more efficient structural excitation.

Correlation Comparison

| Property | TBL (Corcos) | DAF |

|---|---|---|

| Decay Shape | Exponential | Sinc (oscillating) |

| Directional? | Yes (anisotropic) | No (isotropic) |

| Convection | Yes (phase shift) | No |

| Corr. Length |

10. Room Acoustics

Reverberation Time (T60)

Time for sound to decay by 60 dB.

- = Room Volume ()

- = Total Absorption ( Sabins)

Absorption & Room Constant

= Absorption Coeff (0=Reflective, 1=Absorptive)

11. Statistical Energy Analysis (SEA)

High-frequency energy flow method for complex coupled systems.

Power Balance Equation

- = Input Power

- = Damping Loss Factor

- = Coupling Loss Factor

- = Modal Density

- = Total Energy

- Plates (Bending, In-plane)

- Shells (Cylindrical)

- Acoustic Cavities

- Beams

- Point (Beam-Beam)

- Line (Plate-Plate)

- Area (Plate-Cavity)

12. FEA & NASTRAN Dynamics

Solution Sequences (SOL)

| SOL | Description | Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| 103 | Normal Modes | Natural Freqs (), Mode Shapes |

| 108 | Direct Freq. Resp. | Exact solution, freq dependent damping |

| 111 | Modal Freq. Resp. | Efficient for large models (uses modes) |

| 112 | Modal Transient | Time domain shock (uses modes) |

DOF Sets (Matrix Reduction)

Retained DOFs for solution. Contains boundary (R) and dynamic (L) DOFs.

DOFs reduced out via Guyan reduction (static condensation).

Constrained/Boundary DOFs (SPC).

Dependent DOFs defined by MPCs or RBEs.

13. FEA Mesh Guidelines

Elements per Wavelength

| Element Type | Min Elements/λ | Recommended |

|---|---|---|

| Linear (4-node quad) | 6 | 8-10 |

| Quadratic (8-node quad) | 3 | 4-6 |

Wave Types & Speeds

| Wave Type | Speed Equation | Dispersive? |

|---|---|---|

| Longitudinal | No | |

| Shear | No | |

| Bending | Yes | |

| Rayleigh | No | |

| Torsional* | No* |

*Torsional waves are dispersive for non-circular cross-sections due to warping effects.

Critical Bending Wavelength

Bending waves are dispersive (speed varies with frequency). At max frequency:

For plates: where

14. DSP & Data Acquisition

Sampling & Aliasing

Frequencies above fold back (alias) into the baseband.

Dynamic Range & Bit Depth

- = Number of Bits

- 16-bit 96 dB

- 24-bit 144 dB

Window Functions

| Window | Use Case | Trade-off |

|---|---|---|

| Hanning | Random Vib / General | Good amplitude, fair freq |

| Flat Top | Calibration / Sine | Best amplitude, poor freq |

| Rectangular | Transients / Impact | Best freq, leakage risk |

15. Vibroacoustics Scaling Techniques

Franken Method

Empirical method for estimating vibration from acoustic excitation.

Where Y is read from Franken curve at (Hz·ft)

Barrett Scaling

Scales reference PSD to new dynamic pressure conditions.

- = Dynamic pressure

Q-Scaling (SPL)

16. Sensor Selection Guide

Accelerometer Types

| Type | Pros | Cons | Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| IEPE / ICP | Low noise, easy cabling, built-in amp. | Temp limit (~120°C), fixed gain. | General modal, lab testing. |

| Charge | High temp (> 500°C), rugged. | Requires charge amp, noise sensitive cable. | Turbines, engines, shock. |

| MEMS (DC) | Measures DC (gravity), cheap. | Higher noise floor, limited bandwidth. | Automotive, tilt, low freq. |

Selection Criteria

- Sensitivity: 100 mV/g (General) vs 10 mV/g (Shock/High G).

- Range: Max G = 5V / Sensitivity. Ensure .

- Frequency: Check response range. Resonance .

- Mass Loading: Sensor mass test object mass.

17. Structural Engineering Fundamentals

Static Equilibrium

For a body in equilibrium, the sum of all forces and moments must be zero:

Free Body Diagram (FBD) Checklist

- Isolate the body of interest

- Show all external forces (applied loads, reactions)

- Include weight at center of gravity

- Replace supports with reaction forces

- Define positive sign conventions

Support Reactions

| Support Type | Reactions Provided | DOF Constrained |

|---|---|---|

| Roller | 1 force (⊥ to surface) | 1 |

| Pin/Hinge | 2 forces (Fx, Fy) | 2 |

| Fixed/Cantilever | 2 forces + 1 moment | 3 |

Internal Forces

Tension/Compression

Transverse force

Bending

18. Cylinders, Rings, Shells & Cones

Ring Frequency

Frequency at which circumferential wavelength equals the circumference (breathing mode):

- = Longitudinal wave speed in shell material

- = Shell diameter

Critical (Coincidence) Frequency

Frequency where bending wavelength in shell equals acoustic wavelength:

- = Speed of sound in fluid (air ≈ 343 m/s)

- = Shell wall thickness

Shell Behavior Regimes

| Frequency Range | Behavior | Dominant Mode |

|---|---|---|

| Beam-like | n = 1 (bending) | |

| Shell modes | n = 2, 3, 4... (lobar) | |

| Plate-like | High-order modes |

Where is the non-dimensional frequency parameter.

Circumferential Mode Shapes

Breathing

Beam

Ovaling

Lobar

Radiation Efficiency

| Frequency | σ Behavior | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Poor radiator (subsonic bending waves) | ||

| Ring frequency peak | ||

| Coincidence peak | ||

| Efficient radiator |

Ring Stiffener Effects

Adding ring stiffeners shifts natural frequencies:

- = Stiffener spacing

- Creates pass bands and stop bands in frequency response

- Stop bands occur near stiffener resonances

19. Aerospace Material Properties

Common Aerospace Materials (Metric)

| Material | E (GPa) | ρ (kg/m³) | G (GPa) | ν |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al 6061-T6 | 68.9 | 2700 | 26.0 | 0.33 |

| Al 7075-T6 | 71.7 | 2810 | 26.9 | 0.33 |

| Ti-6Al-4V | 113.8 | 4430 | 44.0 | 0.34 |

| Steel 4340 | 205 | 7850 | 80.0 | 0.29 |

| Inconel 718 | 200 | 8190 | 77.0 | 0.30 |

| CFRP (Quasi) | 70 | 1600 | 5.0 | 0.30 |

| Mg AZ31B | 45 | 1770 | 17.0 | 0.35 |

Common Aerospace Materials (English)

| Material | E (Msi) | ρ (lb/in³) | G (Msi) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Al 6061-T6 | 10.0 | 0.098 | 3.77 |

| Al 7075-T6 | 10.4 | 0.102 | 3.90 |

| Ti-6Al-4V | 16.5 | 0.160 | 6.38 |

| Steel 4340 | 29.7 | 0.284 | 11.6 |

| Inconel 718 | 29.0 | 0.296 | 11.2 |

| CFRP (Quasi) | 10.2 | 0.058 | 0.73 |

| Mg AZ31B | 6.5 | 0.064 | 2.47 |

20. Rotating Dynamics

Campbell Diagram

Plot of natural frequencies vs. rotational speed, showing critical speed intersections.

| Component | Description |

|---|---|

| Mode Lines | Natural frequencies that may vary with speed due to stiffening |

| Excitation Lines | 1X, 2X, nX lines representing synchronous excitation |

| Critical Speeds | Intersections where excitation frequency = natural frequency |

| Operating Range | Shaded region showing normal operating speed range |

Blade Mode Stiffening

Centrifugal forces increase blade stiffness with rotational speed:

- = Natural frequency at rest (Ω = 0)

- = Stiffening coefficient (mode-dependent)

- = Rotational speed (rad/s)

Excitation Lines

| Line | Frequency | Typical Source |

|---|---|---|

| 1X | Unbalance, misalignment | |

| 2X | Misalignment, looseness | |

| nX | Blade pass (n = blade count) | |

| Non-integer | Various | Subsynchronous whirl, instabilities |

Example Campbell Diagram

Mode parameters: Mode 1 (f₀=40 Hz, k=0.0001), Mode 2 (f₀=100 Hz, k=0.00005), Mode 3 (f₀=180 Hz, k=0.00002).

Critical speeds: Mode 1 × 1X at 2800 RPM (47 Hz), Mode 2 × 1X at 7000 RPM (117 Hz) - within operating range!

Resonance Condition

Solve for critical speed where excitation line (nX) intersects mode line.

Engineering Review Checklist

- Identify all critical speeds within operating range

- Ensure adequate separation margin (typically 15-20%)

- Check for subsynchronous instabilities

- Verify damping at critical speeds

- Consider transient operation through critical speeds

- Evaluate blade pass frequency interactions

- Account for temperature effects on material properties

21. PSD Calculation from Time History

Welch's Method Overview

Standard approach for estimating PSD from sampled time data using averaged periodograms.

- Preprocess: Remove mean, apply detrending, filter if needed

- Segment: Divide time history into overlapping frames (typ. 50% overlap)

- Window: Apply window function (e.g., Hanning) to each segment

- FFT: Compute FFT for each windowed segment:

- Power: Calculate |Xk|² for each segment

- Average: Average the power spectra across all segments

- Scale to PSD: Convert to single-sided PSD with window energy correction:

where CE = window energy correction factor (see table below), fs = sample rate, N = FFT length. Factor of 2 converts to single-sided (positive frequencies only). For Hanning window, CE = 1.63.

Key Parameters

| Parameter | Formula | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Frequency Resolution | T = segment duration, N = samples/segment | |

| Segment Duration | Longer T → finer Δf but fewer averages | |

| Nyquist Frequency | Maximum resolvable frequency | |

| N for desired Δf | Must be power of 2 for efficient FFT |

Segment duration T = 1024/4000 = 0.256 seconds

Time vs. Frequency Resolution Trade-off

Fundamental trade-off: finer frequency resolution requires longer segments, reducing time resolution and number of averages.

The uncertainty principle: cannot have arbitrarily fine resolution in both domains simultaneously.

| Δf | Segment T | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Hz | 1.0 sec | Fine frequency detail, resolves closely-spaced peaks | Fewer averages, higher variance, poor for short events |

| 5 Hz | 0.2 sec | Good balance for most applications | May not resolve narrow-band features |

| 25 Hz | 0.04 sec | Many averages, low variance, captures transients | Smears frequency content, poor peak resolution |

SMC-S-016 Flight Data Processing

Per SMC-S-016 "Test Requirements for Launch, Upper-Stage, and Space Vehicles":

- Segment Duration: "Use 1-second time segments" for computing PSDs from flight data

- Overlap: "50% overlap between adjacent segments" to maximize statistical DOF

- Bandwidth: 5 Hz constant bandwidth with conversion to 1/6th octave bands for final presentation (no need to go narrower than 5 Hz at low frequencies)

- Window: Hanning window recommended to reduce spectral leakage

Window Functions

Windows reduce spectral leakage from discontinuities at segment boundaries. Each window trades off main lobe width vs. side lobe suppression.

| Window | Amp. Corr. | Energy Corr. | ENBW | Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rectangular | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | Transients (full capture) |

| Hanning | 2.00 | 1.63 | 1.50 | Random vibration (most common) |

| Hamming | 1.85 | 1.59 | 1.36 | General purpose |

| Blackman | 2.80 | 1.97 | 1.73 | Low leakage required |

| Flat Top | 4.18 | 2.26 | 3.77 | Amplitude accuracy (calibration) |

ENBW = Equivalent Noise Bandwidth (in frequency bins). For PSD, apply energy correction.

Overlap & Degrees of Freedom

Overlap reuses data between segments, increasing effective DOF for the same total duration.

| Overlap | DOF per Frame | Efficiency | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0% | 2.00 | 100% | No data reuse |

| 50% | ~1.85 | ~185% | Optimal for Hanning window |

| 75% | ~1.20 | ~240% | Diminishing returns |

where navg = number of averaged segments, ηoverlap = overlap efficiency factor

Higher DOF = lower variance = smoother PSD estimate

PSD Confidence Intervals

PSD estimates follow chi-squared distribution with nDOF degrees of freedom.

| DOF | 90% CI (dB) | 95% CI (dB) |

|---|---|---|

| 10 | ±2.6 | ±3.2 |

| 50 | ±1.1 | ±1.3 |

| 100 | ±0.8 | ±0.9 |

| 200 | ±0.5 | ±0.6 |

Preprocessing & Filtering

| Mean Removal | Subtract DC offset to prevent low-frequency bias. Critical before windowing as DC leaks into adjacent bins. |

| Detrending | Remove linear/polynomial trends from sensor drift. Use least-squares fit for polynomial order 1-3. |

| Anti-Alias Filter | Applied during acquisition. Cutoff fc = 0.4–0.45 × fs typical. Use steep rolloff (8th order Butterworth or better) to ensure >80 dB attenuation at Nyquist. |

| Highpass Filter | Remove content below analysis band. Set cutoff at 0.5–1× lowest frequency of interest. Use 4th order Butterworth (24 dB/octave) minimum. |

Anti-Aliasing Filter Selection

Rule of thumb: fc = 0.4 × fs provides margin for filter rolloff.

| Sample Rate (fs) | Recommended Cutoff | Usable Bandwidth |

|---|---|---|

| 1,000 Hz | 400 Hz | 5–400 Hz |

| 4,000 Hz | 1,600 Hz | 5–1,600 Hz |

| 10,000 Hz | 4,000 Hz | 5–4,000 Hz |

| 50,000 Hz | 20,000 Hz | 5–20,000 Hz |

Higher order filters allow cutoff closer to Nyquist but introduce phase distortion. For shock/transient data, use linear-phase (FIR) filters.

DC & Low-Frequency Handling

- DC Offset: Always remove mean before FFT. Even small DC offsets create large low-frequency artifacts due to spectral leakage.

- Sensor Drift: Accelerometers exhibit 1/f noise below ~5 Hz. Apply highpass filter or discard bins below analysis band.

- Integration Effects: When integrating acceleration to velocity/displacement, DC and low-frequency errors accumulate. Highpass filter before integration.

- Recommended Practice: Set analysis lower bound at 5–10 Hz for typical accelerometer data unless sensor is specifically rated for lower frequencies.

22. SRS CALCULATION FROM TIME HISTORY

What is a Shock Response Spectrum?

The Shock Response Spectrum (SRS) characterizes a transient's potential to excite resonant structures. It plots the peak response of an array of single degree-of-freedom (SDOF) oscillators, each with a different natural frequency but the same damping ratio, when subjected to the same base excitation.

Key concept: The SRS does not contain all information about the original time history—many different transients can produce the same SRS. It captures only the peak instantaneous responses at each frequency.

Smallwood Ramp Invariant Algorithm

The most widely used SRS calculation method is the ramp invariant digital recursive filter developed by David O. Smallwood (1981). This method connects impulse-response samples with straight lines to reduce aliasing errors.

- Define Parameters: Set damping ratio ξ (typically 5%, Q=10) and analysis frequencies

- Design Filter: For each natural frequency fn, compute ramp invariant filter coefficients

- Apply Filter: Process the acceleration time history through each SDOF digital filter

- Extract Peaks: Record maximum positive, negative, and absolute (maximax) responses

- Build Spectrum: Plot peak response vs. natural frequency on log-log axes

SDOF Response Equation

Each oscillator in the SRS bank follows the equation of motion:

where z = relative displacement, ωn = 2πfn, ζ = damping ratio, and ẍbase = input acceleration.

The SRS plots absolute acceleration because it directly relates to the forces experienced by internal components. For a component of mass m mounted on a resonant structure, the force is F = m·ẍabsolute. Relative displacement z is useful for clearance/sway space analysis, but absolute acceleration determines whether components survive the shock. This is why shock test specifications are written in terms of acceleration SRS—they define the maximum forces that equipment must withstand.

Q Factor & Damping

The quality factor Q defines the sharpness of resonance and is related to damping ratio:

| Q Factor | Damping ζ | Application |

|---|---|---|

| Q = 10 | 5% | Standard for pyrotechnic shock (ISO 18431-4, MIL-STD-810) |

| Q = 25 | 2% | Lightly damped structures, conservative analysis |

| Q = 50 | 1% | Very lightly damped, electronic components |

| Q = 5 | 10% | Heavily damped systems, transportation shock |

Higher Q = sharper peaks, more conservative SRS. An SRS plot is incomplete without specifying Q.

SRS Types

| Type | Definition | Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Maximax | max(|positive|, |negative|) over entire duration | Most common, conservative envelope |

| Primary | Peak response during shock application | Forced response analysis |

| Residual | Peak response after shock ends (free vibration) | Ringing/settling analysis |

| Positive | Maximum positive response | Tensile stress analysis |

| Negative | Maximum negative response | Compressive stress analysis |

Frequency Spacing

SRS frequencies are logarithmically spaced in fractional octave bands:

where n = points per octave (e.g., n=6 for 1/6 octave spacing)

| Spacing | Points/Octave | Ratio | Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1/1 Octave | 1 | 2.000 | Coarse overview |

| 1/3 Octave | 3 | 1.260 | General analysis |

| 1/6 Octave | 6 | 1.122 | Standard (ISO 18431-4) |

| 1/12 Octave | 12 | 1.059 | Fine resolution |

| 1/24 Octave | 24 | 1.029 | High resolution |

Sample Rate Requirements

The input time history must be sampled fast enough to accurately capture the shock and compute responses at high frequencies:

- Minimum: fs ≥ 10 × fmax (highest SRS frequency)

- Recommended: fs ≥ 20 × fmax for accurate peak capture

- Example: For SRS to 10 kHz, sample at ≥100 kHz (preferably 200 kHz)

| Max SRS Freq | Min Sample Rate | Recommended | Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 kHz | 20 kHz | 40 kHz | Transportation shock |

| 10 kHz | 100 kHz | 200 kHz | Pyrotechnic shock |

| 100 kHz | 1 MHz | 2 MHz | Near-field pyroshock |

When the sample rate is less than 10× the highest analysis frequency, the digital filter underestimates the true peak response. A correction factor can be applied:

| fs/fn Ratio | Correction Csr | Error if Uncorrected |

|---|---|---|

| 20 | 1.004 | -0.4% |

| 10 | 1.017 | -1.7% |

| 8 | 1.026 | -2.6% |

| 5 | 1.067 | -6.3% |

| 4 | 1.111 | -10% |

| 3 | 1.209 | -17% |

Recommendation: Apply Csr correction when fs/fn < 10. Below ratio of 5, consider resampling/interpolating the time history before SRS calculation for more reliable results. The sinc correction accounts for the averaging effect of discrete sampling on peak values.

Typical Frequency Ranges

| Shock Type | Frequency Range | Typical Q |

|---|---|---|

| Transportation (drop, handling) | 1 Hz – 500 Hz | Q = 5–10 |

| Seismic | 0.1 Hz – 100 Hz | Q = 5–10 |

| Pyrotechnic (far-field) | 100 Hz – 10 kHz | Q = 10 |

| Pyrotechnic (near-field) | 100 Hz – 100 kHz | Q = 10 |

| Ballistic shock | 10 Hz – 50 kHz | Q = 10 |

Velocity & Displacement SRS

SRS can be computed for velocity or displacement by integrating the acceleration response:

| Pseudo-Velocity | |

| Pseudo-Displacement |

Pseudo-velocity SRS is useful for assessing structural stress (σ ∝ velocity). Tripartite plots show all three on one graph.

50 IPS Shock Severity Threshold

The "50 inches per second" (50 IPS) rule is a widely-used empirical threshold for assessing shock severity and potential for damage:

| Pseudo-Velocity | Severity | Typical Concern |

|---|---|---|

| < 20 IPS | Low | Generally benign for most equipment |

| 20–50 IPS | Moderate | May cause fatigue damage with repeated exposure |

| 50–100 IPS | High | Potential yield stress in structural elements |

| > 100 IPS | Severe | Likely permanent deformation or failure |

Preprocessing for SRS

| Mean Removal | Remove DC offset before processing. DC creates artificial low-frequency content. |

| Zero Padding | Extend time history with zeros after shock to capture residual response (typically 2× shock duration). |

| Anti-Alias Filter | Ensure data was acquired with proper anti-aliasing (fc < 0.4 × fs). |

| Integrity Check | Positive and negative SRS should be similar for symmetric pulses. Large asymmetry may indicate clipping or sensor issues. |

23. SOUND TRANSMISSION LOSS

Definition

Sound Transmission Loss (TL or STL) quantifies the reduction in sound power as it passes through a partition:

where τ is the transmission coefficient (ratio of transmitted to incident sound power)

Transmission Loss Regions for Isotropic Panels

The TL behavior of a panel varies with frequency, exhibiting four distinct regions:

| Region | Frequency Range | Controlling Factor | TL Behavior |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stiffness Controlled | f < f1 (first resonance) | Panel bending stiffness | TL decreases with frequency |

| Resonance Region | Near f1 | Panel resonances | TL dip at panel modes |

| Mass Law | f1 < f < fc | Panel surface mass | +6 dB per octave |

| Coincidence Region | f ≈ fc | Wave matching | TL dip (minimum) |

| Damping Controlled | f > fc | Internal damping | +9 dB per octave |

Mass Law

In the mass-controlled region, TL depends primarily on surface density and frequency:

where m'' = surface mass density (kg/m²), f = frequency (Hz)

- Doubling mass → +6 dB TL

- Doubling frequency → +6 dB TL

- Field incidence (random) reduces TL by ~5 dB vs. normal incidence

Critical (Coincidence) Frequency

Coincidence occurs when the acoustic wavelength in air matches the bending wavelength in the panel:

where c = speed of sound in air (~343 m/s), h = panel thickness, ρ = panel density, D = bending stiffness, E = Young's modulus, ν = Poisson's ratio

| Material | fc × h (Hz·mm) | 1 mm plate fc | 10 mm plate fc |

|---|---|---|---|

| Steel | ~12,400 | 12.4 kHz | 1.24 kHz |

| Aluminum | ~12,000 | 12.0 kHz | 1.20 kHz |

| Glass | ~12,700 | 12.7 kHz | 1.27 kHz |

| Plywood | ~20,000 | 20 kHz | 2.0 kHz |

| Gypsum board | ~35,000 | 35 kHz | 3.5 kHz |

TL at Coincidence

At the critical frequency, TL depends strongly on damping:

where η = loss factor. Higher damping reduces the coincidence dip.

| Loss Factor η | Coincidence Penalty | Typical Material |

|---|---|---|

| 0.001 | -27 dB | Steel, aluminum |

| 0.01 | -17 dB | Glass |

| 0.03 | -12 dB | Concrete |

| 0.1 | -7 dB | Damped steel |

| 0.3 | -2 dB | Heavily damped composite |

Above Coincidence (Damping Controlled)

Above the critical frequency, TL increases at approximately 9 dB per octave:

The 9 dB/octave slope comes from: 6 dB/octave (mass law) + 3 dB/octave (damping term)

First Panel Resonance

For a simply-supported rectangular panel:

where a, b = panel dimensions, D = Eh³/12(1-ν²) = bending stiffness

Design Strategies

| Strategy | Effect on TL | Trade-offs |

|---|---|---|

| Increase mass | +6 dB per doubling | Weight penalty |

| Add damping | Reduces coincidence dip | Cost, weight |

| Double-wall construction | +12 dB/octave above mass-air-mass resonance | Thickness, complexity |

| Constrained layer damping | Raises TL at/above fc | Weight, cost |

| Sandwich construction | Shifts fc lower, higher stiffness | Complex coincidence behavior |

Double-Wall Construction

Double-wall partitions provide significantly higher TL than single walls of equivalent mass by decoupling the two panels with an air gap.

Mass-Air-Mass Resonance

The air gap acts as a spring between the two panel masses, creating a resonance at:

where d = air gap depth, m₁, m₂ = panel surface masses (kg/m²), ρair ≈ 1.21 kg/m³, c ≈ 343 m/s

TL Behavior by Frequency Region

| Region | Frequency Range | TL Behavior |

|---|---|---|

| Below f₀ | f < f₀ | Follows combined mass law (~6 dB/octave) |

| At Resonance | f ≈ f₀ | TL dip (panels move in phase) |

| Above f₀ | f > f₀ | ~12 dB/octave (6 dB mass + 6 dB decoupling) |

Simplified Double-Wall TL (above f₀)

where TL₁, TL₂ = individual panel mass law TL values

Design Guidelines

| Parameter | Effect | Recommendation |

|---|---|---|

| Air gap depth | Larger d → lower f₀ | Maximize gap (50-100 mm typical) |

| Panel mass ratio | Dissimilar masses broaden improvement | Use different thicknesses/materials |

| Cavity absorption | Reduces cavity resonances | Add fiberglass/mineral wool |

| Structural bridges | Short-circuit decoupling | Minimize rigid connections |

| Edge sealing | Flanking paths reduce TL | Seal all gaps and penetrations |

24. INSERTION LOSS

Definition

Insertion Loss (IL) quantifies the reduction in sound pressure level at a receiver location due to the insertion of an acoustic treatment (barrier, enclosure, silencer):

where Lp,before = SPL without treatment, Lp,after = SPL with treatment

Barrier Insertion Loss

Sound barriers reduce noise by blocking the direct path and forcing sound to diffract over the top edge.

Fresnel Number

The key parameter for barrier performance is the Fresnel number:

where δ = path length difference (A+B-d), λ = wavelength, f = frequency, c = speed of sound

Path Difference Geometry

δ = A + B - d

A = source to barrier top, B = barrier top to receiver, d = direct path (source to receiver)

Maekawa's Empirical Formula

For a thin, rigid barrier with N > 0 (receiver in shadow zone):

Valid for 0.01 ≤ N ≤ 12.5, point source, no ground reflections

ISO 9613-2 Barrier Formula

More accurate formula accounting for ground and meteorological effects:

where z = path difference, C₂ = 20 (single diffraction), C₃ = 1 for single edge, Kmet = meteorological correction

| Fresnel Number N | IL (Maekawa) | Typical Application |

|---|---|---|

| 0.01 | 5 dB | Grazing incidence |

| 0.1 | 8 dB | Low barrier |

| 1.0 | 13 dB | Moderate barrier |

| 10 | 23 dB | High barrier, high frequency |

| 100 | 33 dB | Very effective barrier |

Enclosure Insertion Loss

Acoustic enclosures surround a noise source to contain radiated sound.

Ideal Enclosure (No Leaks)

where TL = transmission loss of enclosure walls, S = enclosure surface area, R = room constant of interior

Simplified Enclosure IL

For enclosures with internal absorption:

where ᾱ = average absorption coefficient inside enclosure

| Enclosure Type | Typical IL | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Light sheet metal (no absorption) | 10-15 dB | Limited by internal reverb |

| Sheet metal + internal lining | 15-25 dB | 2" fiberglass typical |

| Double-wall with absorption | 25-40 dB | High-performance |

| Lead-lined/composite | 35-50 dB | Critical applications |

Silencer/Muffler Insertion Loss

Silencers attenuate sound in ducts and exhaust systems through reactive and dissipative mechanisms.

Dissipative Silencer (Lined Duct)

Attenuation per unit length for rectangular duct with absorptive lining:

where α = absorption coefficient, P = lined perimeter, S = open area, L = length

Reactive Silencer (Expansion Chamber)

Simple expansion chamber transmission loss:

where m = S₂/S₁ = expansion ratio, k = 2πf/c = wavenumber, L = chamber length

| Silencer Type | Mechanism | Typical IL | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lined duct | Dissipative | 3-10 dB/m | Mid-high frequency |

| Expansion chamber | Reactive | 5-25 dB (tuned) | Low frequency tones |

| Helmholtz resonator | Reactive | 10-30 dB (narrow band) | Specific frequencies |

| Combination | Both | 15-40 dB | Broadband + tones |

Design Guidelines

| Treatment | Key Design Factor | Common Pitfall |

|---|---|---|

| Barriers | Maximize path difference δ | Flanking paths around ends |

| Enclosures | Seal all gaps, add internal absorption | Leaks dominate at high TL |

| Silencers | Match to frequency content | Flow noise regeneration |

25. FEA Best Practices for Dynamic Analysis

Guidance for building FE models from CAD for modal and modal transient analysis.

Element Type Selection

| Structure Type | Recommended Element | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Thin-walled (t/L < 0.1) | CQUAD4, CTRIA3 | Shell elements capture bending efficiently |

| Thick structures | CHEXA, CPENTA | Use when t/L > 0.1 or 3D stress needed |

| Slender members | CBAR, CBEAM | L/d > 10; include shear deformation for short beams |

| Stiffeners on panels | CBEAM on shell | Offset to mid-plane; check eccentricity |

| Fastener patterns | CBUSH, CFAST | Avoid over-stiffening with RBE2 |

Composite Modeling

| Card | Use Case | Key Inputs |

|---|---|---|

| PCOMP | Standard layup | MIDi, Ti, THETAi per ply; Z0 offset |

| PCOMPG | Global ply IDs | Same as PCOMP + global ply tracking |

| MAT8 | Orthotropic 2D | E1, E2, G12, NU12, RHO |

- Define fiber direction (0°) consistently—typically along primary load path

- Use symmetric layups to avoid bend-twist coupling artifacts

- For equivalent smeared properties: use [A], [B], [D] matrices from CLT

Joint Modeling

| Joint Type | Modeling Approach | Stiffness Guidance |

|---|---|---|

| Bolted (stiff) | RBE2 or CBUSH | K ≈ E·A/L for axial; include preload effects |

| Bolted (flexible) | CBUSH with K, B | Huth/Swift formula for shear flexibility |

| Bonded | Tied contact or RBE2 | Assume rigid unless adhesive layer modeled |

| Spot welds | CWELD, CFAST | Diameter-based stiffness; check nugget size |

| Interference fit | CBUSH radial | K = p·π·d·L/δ (pressure-based) |

Damping Specification

| Method | Card/Field | When to Use |

|---|---|---|

| Modal (ζ) | TABDMP1 | Frequency-dependent ζ; most common for modal FRF |

| Structural (G) | GE on MAT1, PARAM G | Constant loss factor η = 2ζ; hysteretic |

| Viscous (B) | CBUSH, CDAMP | Discrete dashpots; shock absorbers |

| Rayleigh (α, β) | PARAM ALPHA1/2 | [C] = α[M] + β[K]; use with caution |

Unit Consistency & Critical Parameters

| System | Length | Mass | Force | Time | WTMASS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SI | m | kg | N | s | 1.0 |

| SI-mm | mm | tonne | N | s | 1.0 |

| SI -mm (kg) | mm | kg | mN | s | 0.001 |

| English (slinch) | in | slinch | lbf | s | 1.0 |

| English (lbm) | in | lbm | lbf | s | 1/386.4 |

WTMASS converts density units:

| Parameter | Purpose | Recommended |

|---|---|---|

| AUTOSPC | Auto-constrain singularities | YES (review .f06 for warnings) |

| MAXRATIO | Max stiffness ratio check | 1.0E7 (default); lower for ill-conditioned |

| BAILOUT | Stop on singularity | -1 (stop) for debugging |

| RESVEC | Residual vectors | YES for modal methods with concentrated loads |

| COUPMASS | Coupled mass matrix | 1 for rotational inertia accuracy |

Model Simplifications

Add mass without stiffness for paint, insulation, wiring. Use NSM field on PSHELL/PCOMP or CONM2 elements.

Constrain out-of-plane translation and in-plane rotations at symmetry plane. Halves model size.

Represent equipment as point masses. Include moments of inertia (I11, I22, I33) for large items.

Use superelements for repeated components or supplier-provided reduced models.

Model Checkout Checklist

| Check | Method | What to Look For |

|---|---|---|

| Free-Free Modes | SOL 103, no SPCs | 6 rigid body modes < 1 Hz (ideally < 0.01 Hz); 7th mode is 1st flex |

| Mass Properties | GPWG output | Total mass, CG location, MOI vs. CAD/hand calc (within 1-2%) |

| Strain Energy | ESE output | Identify elements with high strain energy; check for stress concentrations |

| Grid Point Singularity | AUTOSPC output | Review constrained DOFs; may indicate missing connections |

| Epsilon Check | EPSILON in .f06 | Should be < 1E-8; larger values indicate numerical issues |

| Max/Min Checks | MAXMIN output | Extreme values may indicate bad elements or units |

| 1g Static Load | SOL 101, GRAV card | Reaction forces = total weight; deflection reasonable |

26. Craig-Bampton Component Mode Synthesis

Model reduction technique for efficient dynamic analysis of large, complex assemblies.

Theory Overview

Craig-Bampton (CB) reduces a component's DOFs to boundary DOFs plus a truncated set of fixed-interface normal modes. The transformation preserves dynamic behavior at interfaces while dramatically reducing model size.

Eigenvectors from SOL 103 with boundary DOFs fixed (SPC). Capture internal dynamics of component.

Static shapes from unit displacement at each boundary DOF. Capture quasi-static coupling between components.

Governing Equations

Original system partitioned into boundary (b) and interior (i) DOFs:

CB transformation matrix:

where (constraint modes) and = fixed-interface modes

Reduced coordinates: where

Reduced System:

where and

Implementation in Nastran

| Step | Cards/Method | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Define Boundary | ASET or BSET | Interface DOFs retained in reduced model |

| 2. Define Modal DOFs | QSET | Generalized coordinates for fixed-interface modes |

| 3. Create Superelement | SESET, BEGIN SUPER | Partition component from residual structure |

| 4. Reduce | SOL 103 with EXTSEOUT | Outputs .op2/.pch with reduced matrices |

| 5. Assemble | ASSIGN SE, SEBULK | Attach reduced component to system model |

Residual Vectors

Residual vectors augment the CB basis to improve accuracy for loads not well-represented by truncated modes.

Truncated modes may miss response to concentrated loads or high-frequency content. Residual vectors span the "missing" subspace.

PARAM RESVEC YES in Nastran. Automatically computes static response to applied loads and orthogonalizes against mode set.

Residual vector for load {F}:

Captures static response not spanned by retained modes

Modal Truncation Guidelines

| Analysis Type | Frequency Cutoff | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Frequency Response | 1.5-2× fmax | Ensures modes near upper frequency are accurate |

| Transient (shock) | 2-3× fmax | Higher modes contribute to peak response |

| Random Vibration | 1.5× fmax | RMS dominated by resonances within band |

Component Coupling

Reduced components are assembled at shared boundary DOFs:

where [Lk] = Boolean localization matrix mapping component k boundary DOFs to system DOFs

Boundary grids must match exactly (location, DOFs). Use SECONCT for non-matching meshes.

Recover interior DOF responses:

Accuracy Verification

| Check | Method | Acceptance |

|---|---|---|

| Frequency Error | Compare reduced vs. full model modes | < 1% for modes within cutoff |

| MAC (Modal Assurance) | Correlation of mode shapes | > 0.95 for corresponding modes |

| FRF Comparison | Point FRF at key locations | Peaks within 5% amplitude, 1% frequency |

| Static Deflection | Unit load at boundary | < 0.1% error (constraint modes exact for static) |

27. Dimensionless Parameters

Dimensionless parameters enable similarity analysis, scaling between test and flight, and characterization of physical phenomena. They are ratios of competing physical effects.

Reynolds Number (Re)

Ratio of inertial forces to viscous forces. Determines flow regime (laminar vs turbulent).

- = fluid density, = velocity, = characteristic length

- = dynamic viscosity, = kinematic viscosity

| Re Range | Flow Regime | Application |

|---|---|---|

| Laminar (pipe) | Viscous-dominated, predictable | |

| Transitional | Intermittent turbulence | |

| Turbulent (pipe) | Inertia-dominated, chaotic | |

| Flat plate transition | Boundary layer transition |

Mach Number (M)

Ratio of flow velocity to local speed of sound. Determines compressibility effects.

- = speed of sound, = ratio of specific heats (1.4 for air)

- = specific gas constant, = absolute temperature

| Mach Range | Regime | Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Incompressible | Density changes , use Bernoulli | |

| Subsonic | Compressibility corrections needed | |

| Transonic | Mixed sub/supersonic, shocks form | |

| Supersonic | Shock waves, expansion fans | |

| Hypersonic | High-temp effects, dissociation |

Strouhal Number (St)

Ratio of oscillatory inertia to convective inertia. Characterizes vortex shedding and unsteady flows.

- = shedding frequency (Hz), = characteristic length (diameter)

- = flow velocity

| Geometry | St Value | Re Range |

|---|---|---|

| Circular cylinder | 0.18 - 0.22 | |

| Square cylinder | 0.12 - 0.14 | |

| Flat plate (normal) | 0.14 - 0.15 | |

| Sphere | 0.18 - 0.20 |

Helmholtz Number (He)

Ratio of characteristic length to acoustic wavelength. Determines acoustic compactness.

- : Acoustically compact (lumped parameter models valid)

- : Resonance region (cavity modes, Helmholtz resonators)

- : Geometric acoustics (ray tracing valid)

Other Key Parameters

| Parameter | Definition | Physical Meaning | Typical Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Knudsen (Kn) | Mean free path / length | Continuum vs rarefied flow | |

| Prandtl (Pr) | Momentum / thermal diffusivity | Heat transfer (Pr ≈ 0.7 for air) | |

| Nusselt (Nu) | Convective / conductive heat | Heat transfer coefficient | |

| Froude (Fr) | Inertia / gravity | Free surface flows, ships | |

| Weber (We) | Inertia / surface tension | Droplets, sprays, bubbles | |

| Womersley (Wo) | Unsteady / viscous | Pulsatile flow (blood, hydraulics) | |

| Reduced Freq (k) | Unsteadiness parameter | Aeroelasticity, flutter |

Knudsen Number Regimes

| Kn Range | Regime | Modeling Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Continuum | Navier-Stokes, no-slip BC | |

| Slip flow | N-S with slip BC | |

| Transitional | DSMC, Boltzmann | |

| Free molecular | Collisionless kinetic theory |

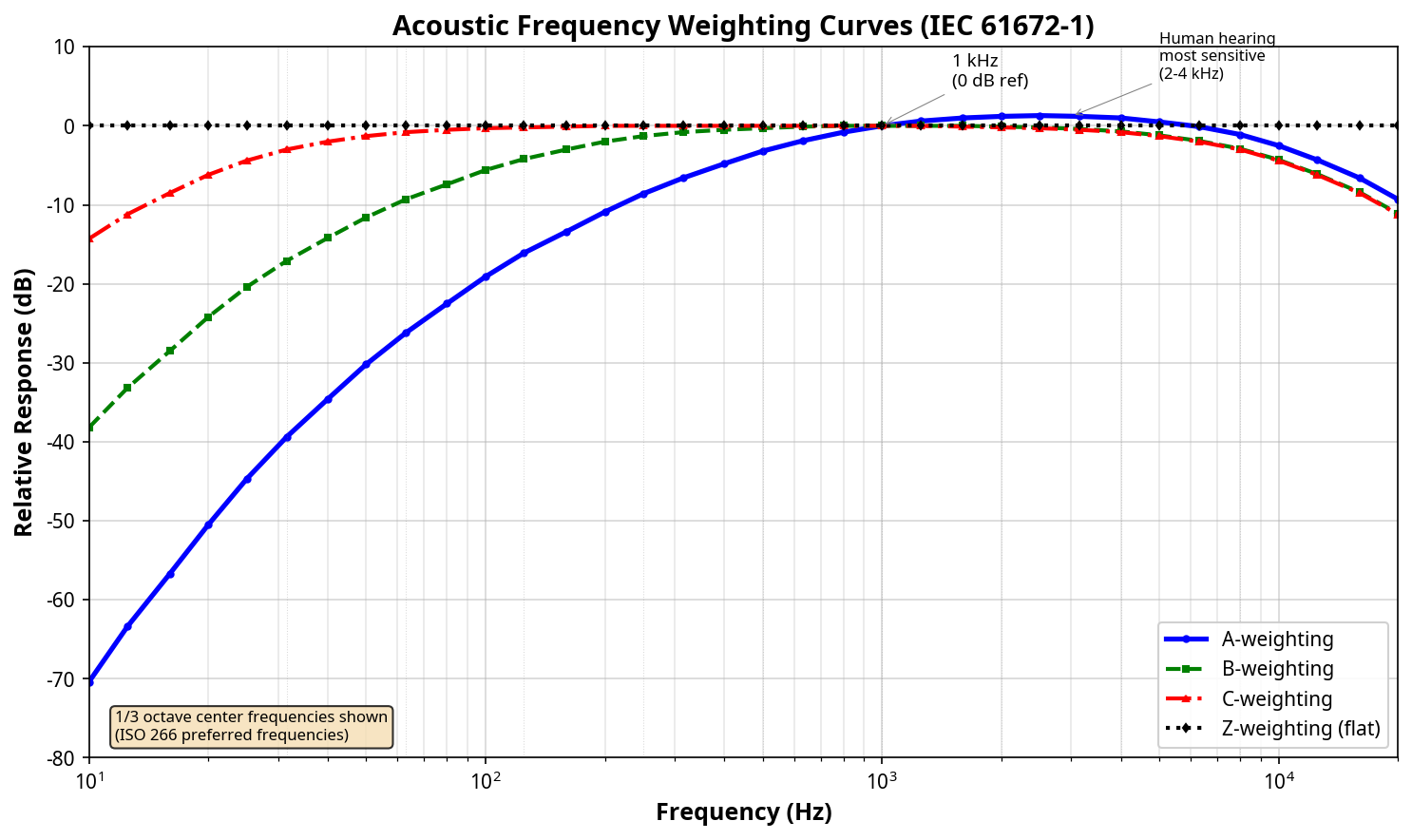

28. Acoustic Weighting Scales

Frequency weighting filters adjust measured SPL to approximate human hearing perception or characterize specific noise types. Defined by IEC 61672-1.

Weighting Curves

| Weighting | Description | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|

| A-weighting (dBA) | Approximates 40-phon equal-loudness contour; attenuates low frequencies heavily | Occupational noise, environmental regulations, hearing damage risk |

| B-weighting (dBB) | Approximates 70-phon contour; moderate low-frequency attenuation | Historical use; largely obsolete (replaced by C) |

| C-weighting (dBC) | Nearly flat response; slight roll-off at extremes | Peak sound levels, low-frequency noise assessment, C-A difference for LF content |

| Z-weighting (dBZ) | Flat (unweighted) from 10 Hz to 20 kHz | Engineering measurements, source characterization, research |

Octave Band Analysis

Acoustic spectra are typically analyzed in octave or fractional-octave bands per ISO 266.

A-Weighting Formula

Analytical approximation (IEC 61672-1):

Normalized to 0 dB at 1 kHz. Maximum response ~+1.2 dB near 2.5 kHz.

Key Values at Standard Frequencies

| Freq (Hz) | A (dB) | C (dB) | Freq (Hz) | A (dB) | C (dB) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 31.5 | -39.4 | -3.0 | 500 | -3.2 | 0.0 |

| 63 | -26.2 | -0.8 | 1000 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 125 | -16.1 | -0.2 | 2000 | +1.2 | -0.2 |

| 250 | -8.6 | 0.0 | 4000 | +1.0 | -0.8 |

Overall Sound Pressure Level (OASPL)

Sum of individual band levels using logarithmic (energy) addition:

- = SPL in each octave band (dB)

- = number of bands

Weighted OASPL: Apply A or C weighting corrections to each band before summing to get dBA or dBC overall level.

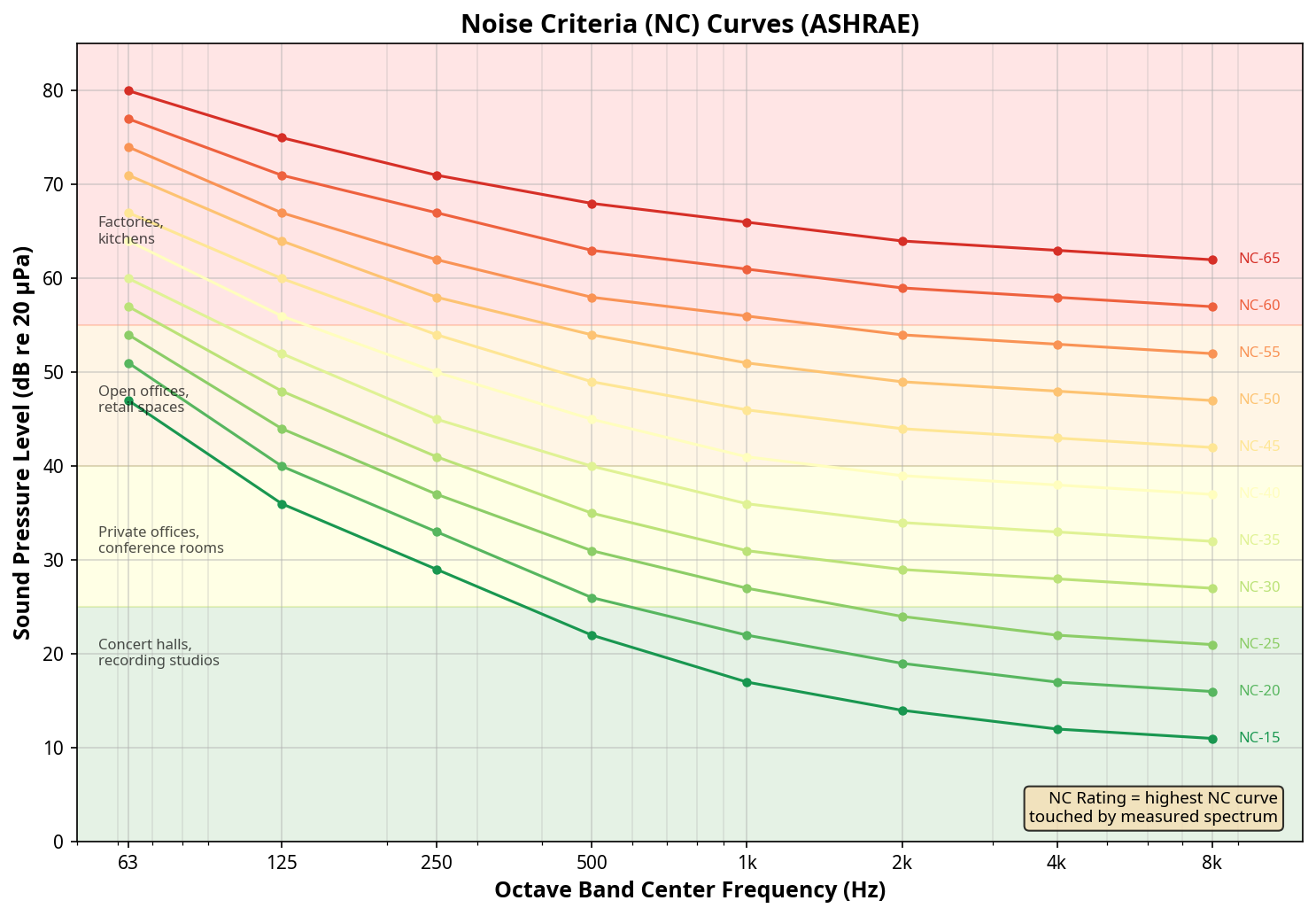

29. Noise Criteria (NC) Curves

NC curves are used to rate background noise in occupied spaces, particularly for HVAC system design. Each curve represents a maximum acceptable SPL at each octave band.

NC Curves (ASHRAE)

Recommended NC Levels by Space Type

| Space Type | NC Range | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Concert halls, recording studios | NC-15 to NC-20 | Critical listening environments |

| Theaters, courtrooms | NC-20 to NC-30 | Speech intelligibility critical |

| Private offices, conference rooms | NC-30 to NC-35 | Confidential speech privacy |

| Open offices, lobbies | NC-35 to NC-45 | Normal speech communication |

| Retail, restaurants | NC-40 to NC-50 | Background masking acceptable |

| Kitchens, laundries, factories | NC-50 to NC-65 | High ambient noise expected |

Related Rating Systems

Improved version addressing rumble (R) and hiss (H) imbalance. Includes quality descriptors.

European/ISO equivalent. Similar shape but different values. NR ≈ NC + 5 approximately.

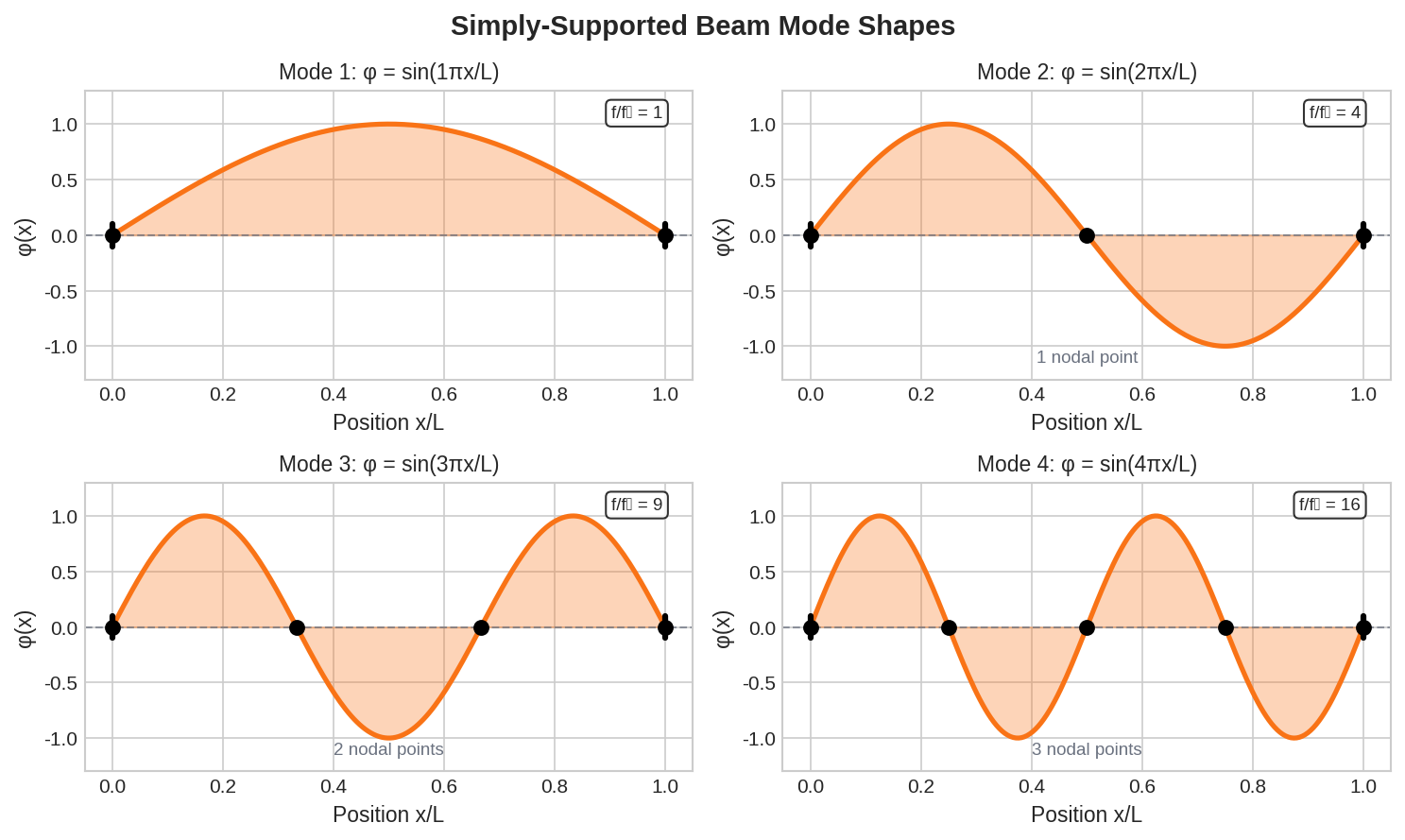

30. Mode Shapes for Beams & Plates

Mode shapes describe the spatial pattern of vibration at each natural frequency. Understanding mode shapes is essential for predicting structural response to dynamic loads and designing effective vibration control.

1D Beam Mode Shapes (Euler-Bernoulli)

For a uniform beam with bending stiffness EI, mass per unit length ρA, and length L, the mode shapes depend on boundary conditions:

Simply-supported beam: first four mode shapes showing nodal points

Simply-Supported (Pinned-Pinned)

Both ends free to rotate but constrained against translation.

| Symbol | Description | Units |

|---|---|---|

| Mode shape function (normalized displacement pattern) | dimensionless | |

| Mode number (1, 2, 3, ...) | integer | |

| Position along beam | m or in | |

| Beam length | m or in | |

| Natural frequency of mode n | Hz | |

| Young's modulus | Pa or psi | |

| Area moment of inertia | m⁴ or in⁴ | |

| Material density | kg/m³ or lb/in³ | |

| Cross-sectional area | m² or in² |

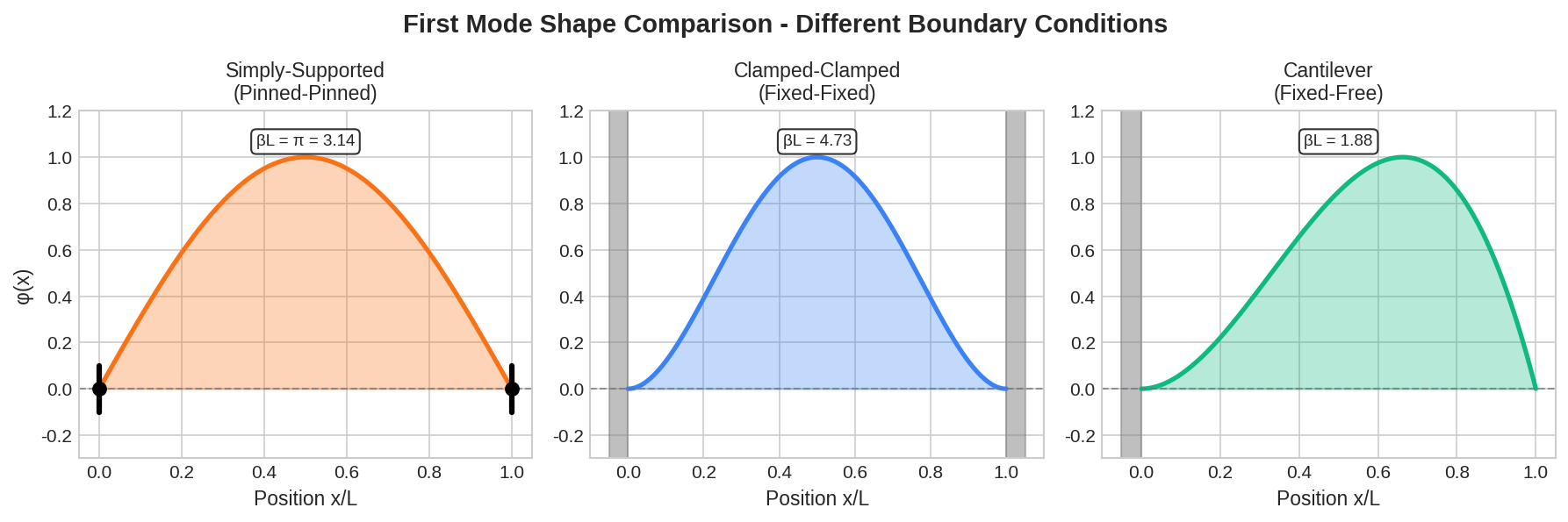

Clamped-Clamped (Fixed-Fixed)

Both ends constrained against rotation and translation.

where satisfies and

| Mode n | Freq. Ratio (rel. to SS mode 1) | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 4.730 | 2.27 |

| 2 | 7.853 | 6.27 |

| 3 | 10.996 | 12.24 |

| 4 | 14.137 | 20.25 |

Cantilever (Fixed-Free)

One end clamped, other end free.

where satisfies

| Mode n | Freq. Ratio (rel. to SS mode 1) | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.875 | 0.356 |

| 2 | 4.694 | 2.23 |

| 3 | 7.855 | 6.27 |

| 4 | 10.996 | 12.24 |

First mode shape comparison: boundary conditions significantly affect both shape and frequency

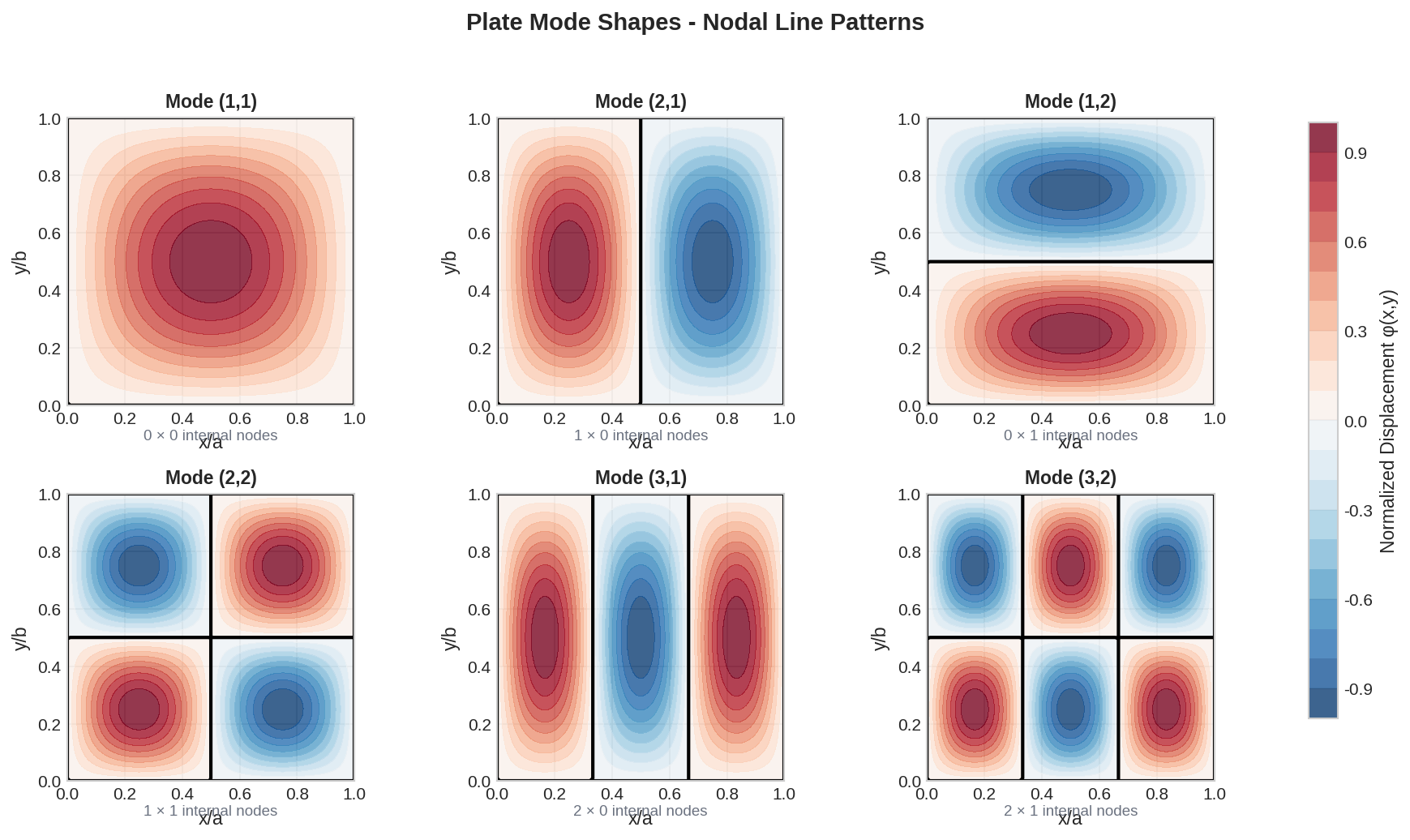

2D Rectangular Plate Mode Shapes

For a thin, isotropic rectangular plate with dimensions a × b, thickness h, and simply-supported edges:

Simply-supported plate mode shapes showing nodal lines (black) where displacement is zero

Simply-Supported Plate (All Edges)

| Symbol | Description | Units |

|---|---|---|

| Mode shape function for mode (m,n) | dimensionless | |

| Mode indices in x and y directions (1, 2, 3, ...) | integers | |

| Plate dimensions in x and y | m or in | |

| Plate thickness | m or in | |

| Flexural rigidity (bending stiffness) | N·m or lb·in | |

| Poisson's ratio | dimensionless | |

| Natural frequency of mode (m,n) | Hz |

Mode Shape Notation

Plate modes are identified by (m,n) where m = half-waves in x-direction, n = half-waves in y-direction:

Fundamental

1 nodal line in x

1 nodal line in y

Cross pattern

Square Plate Frequency Ratios (a = b)

| Mode (m,n) | Frequency Ratio | Nodal Pattern |

|---|---|---|

| (1,1) | 1.00 | No internal nodes |

| (2,1) or (1,2) | 2.50 | 1 nodal line |

| (2,2) | 4.00 | Cross pattern |

| (3,1) or (1,3) | 5.00 | 2 nodal lines parallel |

| (3,2) or (2,3) | 6.50 | Mixed pattern |

| (3,3) | 9.00 | Grid pattern |

Key Concepts

Locations where displacement is zero for a given mode. Higher modes have more nodal lines.

for beams. Determines spatial frequency of mode shape.

Mode shapes are orthogonal: for m ≠ n. Enables modal superposition.

Modes often normalized so (unit modal mass).

Designed for professional reference. Verify all safety-critical calculations.

© 2025 Manus AI Engineering Series.