Maximum Dynamic Pressure (Max Q): The Critical Design Point for Launch Vehicle Vibroacoustics

Understanding Max Q is essential for predicting fluctuating pressure environments and sizing structural components in early vehicle design. This post covers the physics, vehicle class behavior, and how to use the FSP Tool for aeroacoustic analysis.

Every rocket, regardless of its size or mission, must pass through a brief but violent phase during ascent where aerodynamic loads reach their peak. This point, known as Maximum Dynamic Pressure or Max Q, occurs when the competing effects of increasing velocity and decreasing atmospheric density produce the highest aerodynamic forcing on the vehicle structure. For vibroacoustics engineers working on early vehicle design, understanding Max Q is essential for predicting fluctuating pressure environments and sizing structural components.

Disclaimer: The vehicle data presented in this article are compiled from publicly available sources including NASA technical reports, manufacturer payload user guides, and published literature. Actual design parameters and mission-specific values may vary significantly based on payload mass, trajectory optimization, and operational constraints. These values should be used for educational purposes and preliminary analysis only.

The Physics of Dynamic Pressure

Dynamic pressure is defined by the fundamental relationship:

where ρ is the local air density and V is the vehicle velocity. This quantity represents the kinetic energy density of the air relative to the vehicle and directly scales the aerodynamic forces acting on all external surfaces.

During a typical rocket ascent, two competing effects determine the dynamic pressure profile. Atmospheric density decreases exponentially with altitude, roughly halving every 5 km. Meanwhile, vehicle velocity increases approximately linearly as the engines accelerate the rocket. The product of these two trends creates a characteristic peak in dynamic pressure, typically occurring 60 to 80 seconds after liftoff.

For nearly all launch vehicles, regardless of size or propulsion system, Max Q occurs within a remarkably consistent envelope:

| Parameter | Typical Range |

|---|---|

| Altitude | 9 to 14 km |

| Mach Number | 1.2 to 1.6 |

| Dynamic Pressure | 25 to 40 kPa |

| Time After Liftoff | 50 to 90 seconds |

Vehicle Max Q Comparison

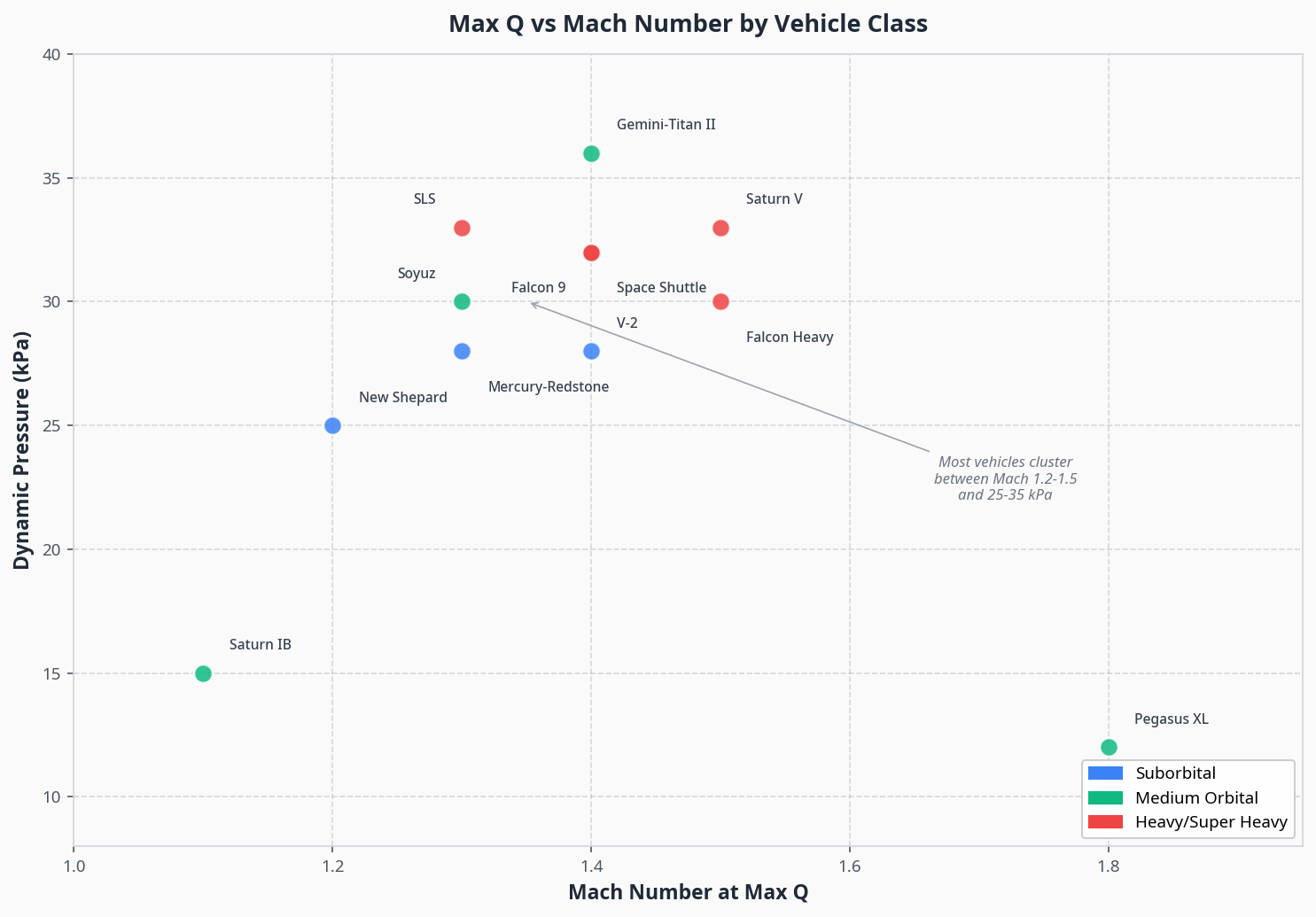

The following chart illustrates how different launch vehicles cluster within a relatively narrow band of Mach number and dynamic pressure at Max Q, despite their vastly different sizes and missions.

| Vehicle | Mach at Max Q | Max Q (kPa) | Vehicle Class |

|---|---|---|---|

| V-2 | 1.4 | 28 | Suborbital |

| Mercury-Redstone | 1.3 | 28 | Suborbital |

| New Shepard | 1.2 | 25 | Suborbital |

| Gemini-Titan II | 1.4 | 36 | Medium Orbital |

| Saturn IB | 1.1 | 15 | Medium Orbital |

| Soyuz | 1.3 | 30 | Medium Orbital |

| Pegasus XL | 1.8 | 12 | Medium Orbital |

| Saturn V | 1.5 | 33 | Heavy/Super Heavy |

| Space Shuttle | 1.4 | 32 | Heavy/Super Heavy |

| Falcon 9 | 1.5 | 30 | Heavy/Super Heavy |

| Falcon Heavy | 1.5 | 30 | Heavy/Super Heavy |

| SLS | 1.3 | 33 | Heavy/Super Heavy |

Key observations from the data:

- All vehicles cluster between Mach 1.1 and 1.8, with most falling in the 1.3 to 1.5 range

- Dynamic pressure ranges from 12 kPa (air-launched Pegasus) to 36 kPa (Gemini-Titan)

- Heavy vehicles with throttle capability tend to cluster around 30-33 kPa

- Suborbital vehicles generally see lower Max Q due to shorter acceleration phases

Why Max Q Matters for Structural Design

The significance of Max Q extends far beyond a single number on a trajectory plot. This brief window of 10 to 20 seconds defines the forcing environment for most hardware on the vehicle. Several critical design considerations are driven by Max Q conditions:

Structural Sizing: The maximum aerodynamic loads determine the required strength and stiffness of fairings, interstages, and external structures. Fairing failures and skin buckling events almost always correlate with the Max Q phase.

Vibroacoustic Forcing: The combination of transonic turbulence and shock-boundary layer interaction produces the highest broadband excitation levels during ascent. Fluctuating pressure environments at Max Q typically exceed those encountered during any other flight phase.

Fatigue Damage: Although brief, the Max Q phase often dominates the fatigue damage spectrum for ascent-loaded components due to the combination of high amplitude and broadband frequency content.

Buffeting: Transonic buffet is strongest when shock waves interact with the turbulent boundary layer, creating unsteady pressure fluctuations that can excite vehicle bending modes.

Vehicle Class Behavior at Max Q

Different vehicle classes have developed various strategies for managing Max Q loads, ranging from simple structural margin to active throttle control.

Suborbital and Sounding Rockets

Early rockets like the V-2 had no throttling capability and relied entirely on structural margin to survive Max Q. The Mercury-Redstone experienced Max Q values around 28 kPa with no active load management. Modern suborbital vehicles like New Shepard encounter Max Q approximately 60 seconds after liftoff at around 10 km altitude, with throttle capability available when needed.

Medium Orbital Vehicles

The Gemini-Titan II experienced Max Q around 36 kPa without throttle control, requiring substantial structural margin. Saturn IB, with its relatively low thrust-to-weight ratio, saw Max Q around 12 km at Mach 1.1 with dynamic pressure near 15 kPa. The Soyuz family, using a core stage with strap-on boosters, encounters Max Q around 30 kPa approximately one minute after liftoff without throttle control.

Air-launched vehicles like Pegasus XL benefit from starting at 12 km altitude, experiencing much lower dynamic pressure despite high Mach numbers.

Heavy and Super Heavy Vehicles

Saturn V encountered Max Q around 33 kPa at approximately 13 km altitude and Mach 1.4 to 1.6. Without throttle capability, the structure was designed to survive these loads directly.

The Space Shuttle introduced active throttle management, with main engines throttled to 65 to 72 percent as dynamic pressure approached Max Q (approximately 30 to 33 kPa at 11 km altitude). The solid rocket booster grain design naturally reduced thrust by one-third after 50 seconds, further limiting peak loads.

Falcon 9 employs a similar throttle bucket strategy, reducing thrust to approximately 70 percent during the Max Q phase. Max Q occurs near 12 km at Mach 1.5 with dynamic pressure around 30 kPa. Falcon Heavy applies the same approach across all 27 engines.

SLS throttles the RS-25 engines down near 50 seconds into flight, encountering Max Q around 33 kPa at Mach 1.3 and approximately 10 km altitude.

Launch Profile Design Rules

Several fundamental rules govern trajectory design through the Max Q region:

-

Gravity turn initiation begins after clearing the launch pad, establishing the pitch profile that carries through Max Q.

-

Angle of attack is tightly limited during the transonic region to minimize asymmetric loads and buffet excitation.

-

Throttle bucket or thrust shaping is almost always centered on the Max Q phase for vehicles with throttle capability.

-

Fairing jettison never occurs until after Max Q, ensuring the payload remains protected during peak aerodynamic loading.

Implications for Early Design and the FSP Tool

For engineers performing early-stage vibroacoustic analysis, the Max Q condition provides the critical design point for fluctuating surface pressure (FSP) predictions. The FSP Tool on this site implements several semi-empirical models that are directly applicable to Max Q environments:

Laganelli Model: Suitable for attached turbulent boundary layer regions on smooth surfaces at the high dynamic pressures typical of Max Q.

Goody Model: Provides wall pressure spectra for turbulent boundary layers, applicable to fuselage and fairing surfaces during transonic flight.

Robertson/Wyle Protuberance Model: Estimates the enhanced fluctuating pressures downstream of surface discontinuities, which experience amplified loading during Max Q.

Separated/Buffet Flow Model: Addresses the separated flow regions that develop at transonic Mach numbers, particularly in base regions and behind geometric transitions.

Rossiter Cavity Model: Predicts tonal excitation from cavities and gaps that can resonate during the transonic Max Q phase.

When using these models for early design, the Max Q flight condition provides the appropriate inputs for dynamic pressure, Mach number, and boundary layer parameters. The resulting fluctuating pressure spectra can then be used to size acoustic blankets, predict structural response, and establish vibration test levels.

Key Insight

All rockets look different on the pad. But between Mach 1 and Mach 1.6 at 10 to 13 km altitude, they all experience the same aerodynamic environment. If your structure survives Max Q, it will likely survive the rest of ascent.

References

-

NASA Glenn Research Center. "Dynamic Pressure." Beginners Guide to Aeronautics. Available at: https://www1.grc.nasa.gov/beginners-guide-to-aeronautics/dynamic-pressure-2/

-

Piatak, D.J., et al. "Ares Launch Vehicle Transonic Buffet Testing and Analysis Techniques." NASA Technical Reports Server, NTRS 20100036691, 2010.

-

Piatak, D.J., et al. "Overview of the Space Launch System Transonic Buffet Environment Test Program." NASA Technical Reports Server, NTRS 20160006923, 2015.

-

Woods, D. and O'Brien, F. "Apollo 8, Day 1: Launch and Ascent to Earth Orbit." Apollo Flight Journal, NASA, 2005.

-

Jackson, D.T. "Space Shuttle Max-Q." Aerodynamics Questions, AerospaceWeb.org, 2001.

-

Heiney, A. "Launch Blog." NASA, 2007. (Space Shuttle throttle-down procedures)

-

SpaceX. Falcon Payload User's Guide. 2025. Available at: https://www.spacex.com/assets/media/falcon-users-guide-2025-05-09.pdf

-

Corcos, G.M. "Resolution of Pressure in Turbulence." Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, Vol. 35, 1963.

-

Blake, W.K. Mechanics of Flow-Induced Sound and Vibration, 2nd Edition. Academic Press, 2017.

-

Lowson, M.V. "Pressure Fluctuations in Turbulent Boundary Layers." NASA Technical Report, 1965.

-

Cockburn, J.A. and Robertson, J.E. "Vibration Response of Spacecraft Shrouds to In-Flight Fluctuating Pressures." Journal of Sound and Vibration, Vol. 33, No. 4, 1974.

-

Wilmarth, W.W. "Pressure Fluctuations Beneath Turbulent Boundary Layers." Annual Review of Fluid Mechanics, Vol. 7, 1975.

-

Lalanne, C. Mechanical Vibration and Shock Analysis, Volume 3: Random Vibration. Wiley-ISTE, 2014.

-

Suresh, B.N. and Sivan, K. "Aerodynamics of Launch Vehicles." In Integrated Design for Space Transportation System, Springer, 2015.

-

Park, S.Y. "Launch Vehicle Trajectories with a Dynamic Pressure Constraint." Journal of Spacecraft and Rockets, Vol. 35, No. 1, 1998.

-

Dukeman, G. "Atmospheric Ascent Guidance for Rocket-Powered Launch Vehicles." AIAA Guidance, Navigation, and Control Conference, AIAA-2002-4559, 2002.

-

Gravante, S.P., et al. "Characterization of the Pressure Fluctuations Under a Fully Developed Turbulent Boundary Layer." AIAA Journal, Vol. 36, No. 10, 1998.

-

Camussi, R., et al. "Wall Pressure Fluctuations Induced by Transonic Boundary Layers." Aerospace Science and Technology, Vol. 11, 2007.

-

Wikipedia contributors. "Max q." Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Max_q

-

Schulman, M. "Saturn V Step-by-Step." Version 1.5, January 2025. NASA History Division.